The morning sun illuminates the stark beauty of Ajo’s landscape, casting long shadows across the open-pit mine that dominates the eastern edge of town. Unlike many of Arizona’s mining communities that flared briefly before fading into ghost towns, Ajo represents a different story—one of remarkable persistence through boom and bust cycles. Nestled in the Sonoran Desert of southwestern Arizona, approximately 43 miles from the Mexican border, this community still stands as a living testament to Arizona’s mining heritage, though much diminished from its heyday. The town’s Spanish name, meaning “garlic” (though some argue it derives from a Tohono O’odham word for paint), reflects the cultural crossroads where Anglo, Mexican, and Native American influences have converged for generations.

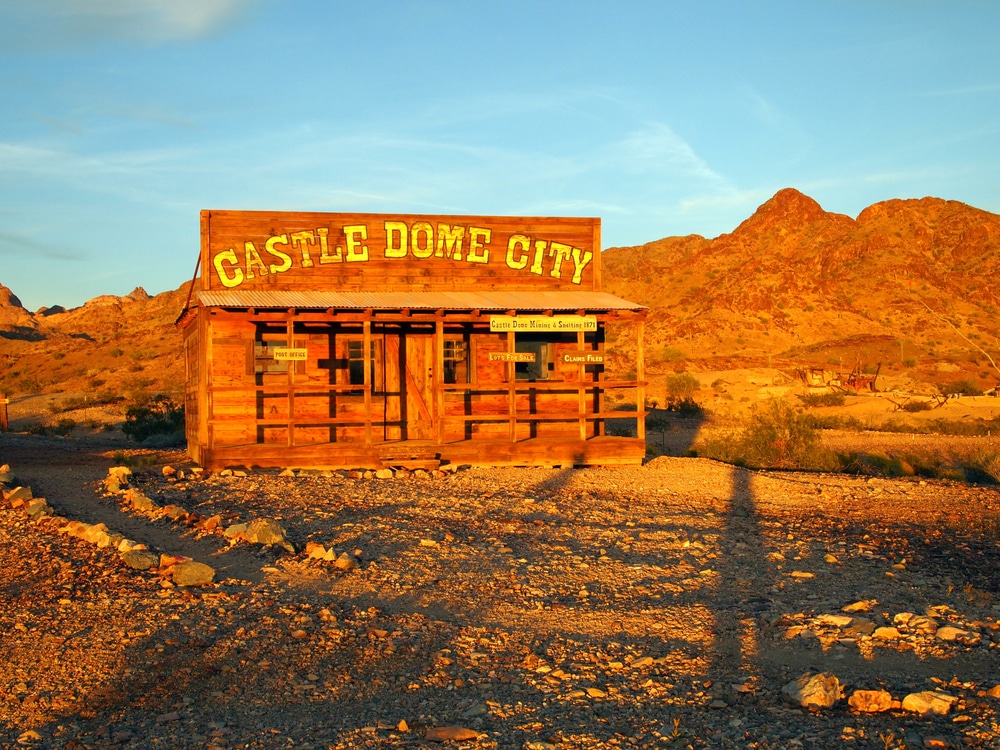

The heart of any visit is the Castle Dome Mine Museum, a sprawling outdoor museum with over 50 reconstructed and restored buildings that recreate life in the late 1800s mining town. Visitors can wander through authentic structures including:

A sheriff’s office and jail

General store and saloon

Schoolhouse and chapel

Blacksmith shop, miners’ cabins, and brothel

Each building is filled with period-correct artifacts, giving a sense of daily life during Arizona’s early mining boom. Interpretive signs and friendly staff bring the history to life.

The museum is built atop the original Castle Dome Mine, which produced significant amounts of silver, lead, and zinc. You can see old mine shafts (safely fenced off), headframes, ore carts, and tools used in the rugged terrain of the Castle Dome Mountains. It’s one of the best places in Arizona to see preserved mining infrastructure in a realistic setting.

A highlight of the museum is the fluorescent mineral exhibit, located underground in one of the original mine shafts. Under blacklight, the minerals glow in brilliant colors—an exciting and educational experience for both kids and adults interested in geology and mining science.

The Castle Dome Mountains provide a stunning backdrop to the ghost town. With their jagged volcanic peaks, saguaro-studded hills, and expansive desert skies, the area is a dream for photographers. The golden hour transforms the ghost town into a cinematic scene straight from the Old West.

The remote location offers opportunities to spot desert wildlife, including hawks, owls, mule deer, coyotes, jackrabbits, and lizards. Birdwatchers will appreciate the peaceful, undeveloped surroundings and the occasional appearance of desert-dwelling raptors and songbirds.

While the museum itself is protected, the surrounding BLM land in the Castle Dome Mountains offers legal areas for rockhounding and mineral collecting. The region is known for its variety of minerals, including wulfenite, fluorite, vanadinite, and colorful quartz specimens.

With almost no light pollution, Castle Dome Landing is a fantastic place for stargazing. After sunset, the skies come alive with stars, constellations, and meteor showers. Bring a telescope or simply recline and enjoy the Milky Way stretching across the sky.

Behind Castle Dome Landing’s commercial statistics and transportation records lie the human stories that give this ghost town emotional resonance. Three individuals in particular exemplify different facets of life in this frontier river port.

Captain Lorenzo Blackmar represents the steamboat era that gave Castle Dome Landing its purpose. Arriving on the Colorado River in 1865 after previous experience on Mississippi riverboats, Blackmar quickly established himself as one of the most skilled navigators of the challenging waterway. Contemporary accounts in both local newspapers frequently mentioned his vessel, the Mohave, as “the most reliable connection to civilization.” Blackmar eventually settled permanently at the Landing, building a substantial home overlooking the river and serving on the informal town council. The Colorado River Journal described him as “a fixture of community life as dependable as the river itself, though considerably less prone to unexpected behavior.” When he died in 1889 after a brief illness, his funeral reportedly drew over 300 mourners—nearly a tenth of the Landing’s population. His grave in the community cemetery features a carved steamboat wheel atop a substantial stone marker, reflecting both his profession and the community’s recognition of his significance.

Elena Vasquez Torres brought different skills to the developing community. Arriving from Sonora, Mexico in 1872, she established the Landing’s first proper restaurant, serving meals that incorporated both Mexican traditions and adaptations using available ingredients. The Castle Dome Sentinel regularly featured advertisements for her establishment, “La Paloma,” which became a gathering place for community discussions and celebrations. Beyond her business success, Torres organized the community’s first school in 1875, initially operating from a corner of her restaurant before leading efforts to construct a dedicated schoolhouse in 1877. When formal teachers were unavailable, she provided basic education herself, ensuring children received at least fundamental literacy and numeracy. Her grave in the community cemetery celebrates her as “Maestra y Madre de la Comunidad” (Teacher and Mother of the Community), acknowledging her diverse contributions to Landing life. Historical records indicate that Torres maintained connections with family in Mexico throughout her life, creating cross-border networks that facilitated trade and cultural exchange even as national identities solidified in the late 19th century.

Lee Wong’s story illuminates both the diversity of Castle Dome Landing and the challenges faced by minority residents in territorial Arizona. Arriving in 1876 during the peak of anti-Chinese sentiment in the American West, Wong established a laundry business that expanded to include a small general store specializing in goods imported from San Francisco’s Chinese merchants. Business records preserved in the Yuma Historical Society collection show his enterprise serving customers from all ethnic backgrounds, becoming an integral part of the community economy despite prevailing prejudices. When exclusionary ordinances threatened Chinese businesses in many Arizona communities in the 1880s, Castle Dome Landing’s practical need for Wong’s services apparently trumped discriminatory impulses. The Sentinel noted in 1882 that “attempts to apply the exclusionary fever from elsewhere to our Chinese neighbors would deprive the Landing of valuable services no others have shown interest in providing.” Wong’s grave in the pioneer cemetery, marked with both English and Chinese characters, dates to 1897—among the last burials in that ground. His final years coincided with the Landing’s decline, with records suggesting his business contracted along with the overall community economy.

These individual stories intersect with broader community narratives documented in newspaper accounts, business records, and personal correspondence. Marriage records reveal cross-cultural relationships that sometimes transcended the period’s racial boundaries, particularly between Hispanic and Anglo residents. Business partnerships frequently crossed ethnic lines, creating economic ties that complicated simplistic notions of frontier segregation. Church records, though fragmentary, indicate how religious institutions both reinforced cultural identities and occasionally bridged community divisions through shared rituals and celebrations.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | Castle Dome Landing, Arizona |

| Type | Restored ghost town / open-air museum |

| County | Yuma County |

| Founded | 1863 (mining began), town grew in 1869 |

| Status | Abandoned as a town; now preserved as a ghost town museum |

| Population (Historic) | ~3,000 at peak in the 1870s |

| Population (Current) | None (non-residential; operated as historical site) |

| Historical Significance | Served as a major mining camp and Colorado River port during Arizona’s silver and lead boom |

| Primary Industry | Lead, silver, zinc mining (especially important during Civil War and WWII) |

| Post Office | Operated from 1875 to 1884 |

| Decline Factors | Ore depletion, isolation, railroad bypass, Colorado River course changes |

| Remnants Today | Over 50 restored buildings, mining artifacts, exhibits, and cemetery |

| Managed As | Castle Dome Mine Museum & Ghost Town (privately owned) |

| Nearby Landmark | Castle Dome Peak, Castle Dome Mountains |

| Access | ~40 miles north of Yuma; accessible by dirt roads (well-maintained) |

| Elevation | Approx. 1,800 feet (549 meters) |

| Climate | Sonoran Desert – extremely hot summers, mild winters |

| Best For | Ghost town tourists, photographers, family travelers, mining history buffs |

Castle Dome Landing’s story begins with the discovery of silver and lead deposits in the nearby Castle Dome Mountains in the early 1860s. Initially prospected by Spanish explorers decades earlier, these mineral riches attracted renewed interest following the Gadsden Purchase of 1854, which brought this territory under American control. The Civil War further accelerated development, as the Union’s need for lead for ammunition created strong market demand for the area’s resources.

By 1864, the Castle Dome Mining District had been officially established, and miners needed a reliable way to transport ore and receive supplies. The logical solution was to create a port on the Colorado River, which served as the region’s primary transportation artery before the arrival of railroads. Thus, Castle Dome Landing was established approximately 20 miles north of Yuma at a natural bend in the river where steamboats could easily dock.

The settlement quickly grew from a simple landing site to a proper community serving as the lifeline for the mining district located about 15 miles to the east in the Castle Dome Mountains. While the mines themselves spawned their own small settlement (Castle Dome City), the Landing became the commercial hub due to its critical transportation function.

At its peak in the 1870s and 1880s, Castle Dome Landing housed approximately 3,000 residents, making it a significant settlement in Arizona Territory and temporarily rivaling Yuma in population and commercial activity. The community featured all the hallmarks of frontier development: mercantile stores, saloons, hotels, blacksmith shops, warehouses, and eventually schools and churches as families joined the initial wave of miners and merchants.

The Landing represented an economic bright spot during Arizona’s territorial period, flourishing while much of the territory struggled with isolation, Apache conflicts, and limited resources. Its development paralleled Arizona’s gradual transition from military outpost to mining region to more diverse economy. The Colorado River steamboat network that sustained Castle Dome Landing was part of a transportation revolution that helped integrate this remote corner of the Southwest into the nation’s economic fabric before railroads rendered river commerce obsolete.

Today, visitors to the former site of Castle Dome Landing will find little to indicate the once-thriving port town. Located on what is now part of the Yuma Proving Ground, a U.S. Army facility, access to the exact location is restricted. The few physical remains include scattered foundation stones, occasional rusted metal artifacts half-buried in the soil, and indentations in the riverbank where docks once stood.

Erosion, flooding, and the construction of modern dams have significantly altered the Colorado River’s course and flow patterns since the Landing’s heyday, further obscuring the historical landscape. The original townsite has been largely reclaimed by desert vegetation, with creosote bushes, mesquite, and invasive tamarisk growing where streets and buildings once stood.

Archaeological surveys conducted in the 1980s documented the rough outline of the settlement, identifying the probable locations of major structures and commercial areas. These studies recovered numerous artifacts including glass bottles, ceramic fragments, metal tools, and personal items that offer glimpses into daily life at the Landing. These findings are now primarily housed in collections at the Yuma Territorial Prison State Historic Park and the Arizona Historical Society.

While Castle Dome Landing itself has virtually disappeared from the physical landscape, the associated mining district has been better preserved. The Castle Dome Mine Museum, established in the late 1990s, has reconstructed portions of the mining camp located in the mountains east of the Landing. This open-air museum features over 50 restored and reconstructed buildings including a church, saloons, assay office, and various miners’ cabins, providing visitors a tangible connection to the region’s mining heritage.

The museum displays many artifacts recovered from both the mines and the Landing area, including cargo manifests from steamboats, mining equipment, household items, and personal effects that illuminate life in this frontier community. While not on the original Landing site, this museum serves as the primary physical link to the vanished river port that once sustained the mining district.

Preservation efforts focus primarily on documentation rather than physical restoration of Castle Dome Landing itself, given its location on active military land and the extreme environmental degradation of the site. Historical research, oral histories from descendants, and archival materials from territorial newspapers and business records constitute the main avenues for preserving the Landing’s legacy.

Approximately half a mile east of where Castle Dome Landing’s main street once ran lies the pioneer cemetery, its boundaries now marked only by scattered stone cairns and a few weather-worn wooden crosses. Established around 1865 when the Landing was still in its infancy, this burial ground received the community’s earliest residents—those who gambled their futures and ultimately their final rest on this remote frontier outpost.

The cemetery occupies a small rise that provided protection from the Colorado River’s unpredictable flooding while offering views of both the river to the west and the Castle Dome Mountains to the east. This intentional placement reflected both practical considerations and symbolic significance, positioning the dead between the transportation lifeline and the mineral wealth that gave purpose to the community.

Archaeological surveys conducted in the 1990s identified approximately forty distinct burials, though local accounts suggest there may be more than sixty graves in total. Most markers have disappeared entirely, victims of harsh weather, occasional flooding, and the unfortunate practice of “souvenir hunting” that plagued many abandoned cemeteries in the early 20th century before preservation ethics evolved.

The oldest identifiable grave belongs to William Pierson, a steamboat crewman who, according to a contemporary newspaper account, drowned in 1866 when he fell overboard during a late-night docking maneuver. His simple marker—a wooden board later replaced with a stone tablet by fellow river workers—exemplifies the constant dangers faced by those who worked the unpredictable Colorado River.

Several graves from 1867-1868 belong to victims of a smallpox outbreak that swept through the Landing, reflecting the vulnerable nature of frontier communities to infectious disease. These graves were reportedly dug slightly apart from others, indicating awareness of contagion even before modern medical understanding.

Most telling about the pioneer cemetery’s demographics is the predominance of men in their twenties and thirties—the miners, riverboat workers, and merchants who formed the backbone of early settlement. The few women buried here largely died in childbirth, a stark reminder of the particular dangers frontier life posed to female settlers. Several small graves indicate children who succumbed to childhood diseases, accidents, or the harsh desert environment.

The cemetery contains evidence of the community’s diverse ethnic makeup. Markers with Spanish inscriptions indicate Mexican miners and merchants, while at least two stones bear Chinese characters—likely belonging to laborers or merchants who established businesses serving the mining community. These graves physically document the multicultural nature of Arizona’s frontier communities often overlooked in traditional histories.

By the late 1880s, burials in the pioneer cemetery had largely ceased as the community established a larger, more formally organized burial ground farther from the river—a sign of the Landing’s growth and increasing stability. Today, the pioneer cemetery lies silent and largely forgotten, its residents’ stories preserved primarily through archaeological documentation and scattered references in territorial newspapers and personal journals.

As Castle Dome Landing matured from roughshod river port to established community, residents established a more formal burial ground approximately two miles east of town around 1885. This “Castle Dome Landing Cemetery,” as it was officially designated, represented the community’s transition toward permanence and respectability, with more elaborate monuments, family plots, and organized record-keeping.

Unlike the pioneer cemetery, the community cemetery followed a planned layout with designated sections, formal pathways, and a small maintenance building that also served as a chapel for funeral services. Historical records indicate that a part-time caretaker maintained the grounds, a position funded through a combination of burial fees and community donations.

The gravestones in the community cemetery tell a different demographic story than those in the pioneer grounds. Here, family plots become common, indicating multi-generational households and more balanced gender representation. Children’s graves remain numerous—a reflection of the high childhood mortality rates that persisted even as the community developed more sophisticated infrastructure and services.

Professional designations appear on many markers—”Steamboat Captain,” “Merchant,” “Assayer,” “Teacher”—reflecting the occupational diversification beyond mining that characterized the maturing community. Religious symbols become more prominent, with crosses, Stars of David, and Masonic emblems indicating the town’s growing religious and social organizations.

The community cemetery contains approximately 150 identifiable graves, though ground surveys suggest as many as 200 individuals may be interred here. The date range spans from 1885 through the early 1900s, with the latest identified burial occurring in 1903, shortly before river transportation declined precipitously with the arrival of the railroad in Yuma.

Burial customs evolved over this period as reflected in both the physical markers and contemporary accounts. Early graves feature simpler headstones with basic information, while later monuments become more elaborate, some featuring poetry, biblical verses, or detailed biographical information. Several graves show evidence of decorative fencing or plantings, indicating ongoing care by family members during the cemetery’s active period.

The cemetery’s multicultural character mirrors the community’s diverse population. Mexican, Chinese, Native American, and European graves share the space, sometimes in culturally distinct sections but increasingly intermingled over time. This integration reflects the pragmatic cooperation that characterized many frontier communities despite the period’s broader patterns of segregation and discrimination.

After the Landing’s decline in the early 1900s, the community cemetery fell into neglect. Unlike the pioneer cemetery, however, it occasionally received new burials through the 1920s as former residents who had relocated to Yuma or other communities requested interment among family members. These sporadic burials helped maintain minimal attention to the grounds, though no formal maintenance continued after about 1910.

Today, the community cemetery remains in better condition than its pioneer counterpart, partly due to its more substantial monuments and partly due to its location farther from the river on slightly higher ground. A 2005 restoration project by the Yuma County Historical Society documented each remaining marker, cleared invasive vegetation, and installed a simple fence and interpretive sign explaining the cemetery’s significance to regional history.

Castle Dome Landing’s written history comes to us primarily through two competing newspapers that chronicled the community’s development, celebrated its successes, and occasionally exposed its shortcomings. The first, the Colorado River Journal, began publication in 1868 as a weekly four-page paper produced by Jacob Rheinhart, a former San Francisco typesetter who saw opportunity in the growing river port.

Operating from a modest adobe building near the main steamboat dock, the Journal positioned itself as the “Voice of Progress along the Colorado,” focusing heavily on mining news, shipping schedules, and mercantile advertisements. Rheinhart maintained a decidedly pro-development editorial stance, consistently advocating for territorial investment in river improvements and government contracts for local mines.

In 1874, as the community continued to grow, a competing publication emerged—the Castle Dome Sentinel—established by Thomas Granger, who had previously worked for newspapers in Prescott. The Sentinel adopted a somewhat more independent editorial position, occasionally criticizing working conditions in the mines and questioning the outsized influence of the large shipping companies that dominated river commerce.

Both papers documented the rhythms of community life, from mining successes and technological improvements to social events and personal milestones. The Journal emphasized economic development, regularly publishing reports on ore quality, production volumes, and steamboat cargo manifests—information crucial to both residents and distant investors. Meanwhile, the Sentinel devoted more space to community news, documenting school activities, church services, and cultural events that increasingly defined life at the Landing beyond its economic functions.

The newspapers played vital roles during periods of regional crisis. During the severe drought and subsequent river navigation challenges of 1875, both publications provided crucial information about water levels, alternative supply routes, and community conservation measures. When smallpox threatened again in 1877, the papers shared prevention advice and documented quarantine measures that helped limit the outbreak.

Editorial positions sometimes reflected competing visions for Castle Dome Landing’s development. The Journal consistently supported the interests of the large mining companies and steamboat lines, advocating for consolidated operations and outside investment. In contrast, the Sentinel more frequently gave voice to independent prospectors, small merchants, and labor concerns, occasionally criticizing the growing influence of absentee ownership in both mining and transportation.

As railroad development reached Arizona Territory in the 1880s, both newspapers actively debated its implications for river commerce. The Journal initially dismissed concerns about rail competition, arguing that the unique advantages of water transportation would preserve the Landing’s economic position. The Sentinel proved more prescient, questioning as early as 1880 whether the community needed to diversify its economic base beyond servicing the mining district and river trade.

The papers documented the gradual shift in the Landing’s fortunes beginning in the late 1880s. Initial optimism about new mining techniques and deeper ore bodies gradually gave way to acknowledgment of declining production and reduced river traffic. By 1895, the Colorado River Journal had reduced from weekly to monthly publication, while the Sentinel continued on a semi-monthly basis with increasingly slim issues.

The final edition of the Journal, published in September 1897, simply stated: “With transportation now centered in Yuma and mining activity reduced to maintenance levels, this publication no longer serves sufficient commercial purpose to continue. We thank our loyal readers these past 29 years and wish prosperity to those who remain at the Landing.” The Sentinel continued publishing until 1901, increasingly focused on Yuma news before finally relocating operations there entirely.

Today, incomplete collections of both newspapers are preserved at the Arizona Historical Society and the Yuma Territorial Prison State Historic Park archives. These yellowed pages provide our most detailed window into daily life, commercial activities, and community concerns during Castle Dome Landing’s existence, capturing voices and perspectives otherwise lost to history.

Castle Dome Landing’s story is inextricably linked to transportation networks—first through its dependence on river navigation and later through its decline in the face of railroad competition. Unlike many Western settlements that owed their existence to railroad expansion, Castle Dome Landing predated trains in Arizona Territory, flourishing instead through the Colorado River steamboat system that served as the region’s commercial lifeline.

From the 1860s through the 1880s, steamboats represented the most efficient transportation option for the isolated southwestern territories. Castle Dome Landing developed specifically to serve as a transfer point between the mines in the Castle Dome Mountains and the steamboats plying the Colorado. Ore would travel by wagon from the mines to the Landing, where it was loaded onto steamboats bound for processing facilities in California. Return trips brought necessary supplies, mail, and passengers to the isolated mining district.

Contemporary accounts describe a bustling port where steamboats docked several times weekly during peak periods. Companies like the Colorado Steam Navigation Company operated vessels specifically designed for the challenging river conditions—shallow-draft stern-wheelers that could navigate the Colorado’s frequent sandbars and changing channels. The most famous of these, the Gila and the Mohave, regularly called at Castle Dome Landing, becoming so integral to community life that their whistles served as time markers for local residents.

The Landing developed specialized infrastructure to support river commerce. Loading docks extended into the river at points where the channel ran close to shore. Warehouses lined the waterfront, storing ore awaiting shipment and supplies destined for the mines. Maintenance facilities provided basic repairs for both steamboats and the wagon teams that connected the Landing to the mining district.

This river-centered transportation network shaped every aspect of community life. Business activities and social events were scheduled around boat arrivals. The Colorado River Journal regularly published steamboat schedules and cargo manifests, information as essential to residents as train timetables would later become in railroad towns. When river conditions delayed boats, the entire community felt the effects through supply shortages and commercial disruptions.

The arrival of railroads in Arizona Territory beginning in the 1880s fundamentally altered this transportation equation. The Southern Pacific Railroad reached Yuma in 1877, connecting it directly to California markets and bypassing the more time-consuming river route. Though Castle Dome Landing was not immediately affected, this development foreshadowed the coming transformation.

The community’s leadership recognized the potential threat and began lobbying for a spur line to connect the Landing and mining district to the main railroad in Yuma. In 1887, survey work began for a proposed Castle Dome Railroad that would run from Yuma to the mines via the Landing. The Colorado River Journal enthusiastically reported these developments, predicting that “the iron horse shall soon complement our faithful steamboats, bringing greater prosperity to our community.”

Construction on the spur line progressed slowly and unevenly, hindered by financial limitations and challenging terrain. By 1892, tracks had reached only halfway to the Landing, creating an awkward transfer point that actually increased transportation complexity rather than reducing it. Meanwhile, mining production in the Castle Dome district began declining as the most accessible ore bodies showed signs of depletion.

In a cruel twist of timing, the partial railroad connection accelerated Castle Dome Landing’s decline rather than reversing it. The rail line made it more efficient to transport ore directly from the mines to Yuma, bypassing the Landing entirely. When the tracks finally reached within a mile of the Landing in 1895, the community had already lost much of its economic purpose.

By 1900, steamboat traffic on the Colorado had dwindled to occasional vessels, primarily serving communities without rail access. Castle Dome Landing, once defined by its river connection, found itself increasingly isolated as both water and rail transportation bypassed it in favor of more direct routes. The final regular steamboat service to the Landing ceased in 1904, effectively ending its function as a transportation hub.

Today, little physical evidence remains of either the steamboat docks or the railroad that arrived too late to save the community. The altered course of the Colorado River has erased most traces of the landing facilities, while the rail line was dismantled for scrap during World War I. This transportation evolution—from river to rail to eventual abandonment—encapsulates the broader patterns of development and decline that characterized many frontier communities in the American West.

Castle Dome Landing’s decline unfolded gradually over approximately fifteen years, from the first indications of mining reduction in the late 1880s to near-abandonment by 1904. This trajectory illustrates the particular vulnerability of communities built around both extractive industries and specific transportation technologies—when either foundation weakened, the settlement’s reason for existence came into question.

The first signs of trouble appeared in the mines themselves. By the late 1880s, the most accessible silver and lead deposits in the Castle Dome district showed signs of depletion. Deeper mining required more substantial investment and technology, increasing production costs just as silver prices began a long-term decline following the Sherman Silver Purchase Act’s implementation and eventual repeal. The Colorado River Journal reported in 1888 that two of the smaller mines had suspended operations, though it characterized this as “temporary adjustment rather than permanent reduction.”

Simultaneously, transportation patterns began shifting following the Southern Pacific Railroad’s arrival in Yuma. Though riverboats continued operating, they faced increasing competition for certain types of cargo, particularly higher-value goods and passenger traffic that benefited from the railroad’s greater speed and reliability. The Castle Dome Sentinel noted in 1890 that “steamboat arrivals have reduced from thrice weekly to twice weekly, reflecting the diverted traffic now moving by rail.”

The partial completion of the spur line toward Castle Dome in the early 1890s accelerated these changes rather than reversing them. The half-finished rail connection created a hybrid transportation route that ultimately favored Yuma over the Landing as the principal shipping point. By 1895, the Colorado River Journal acknowledged that “weekly steamboat service now suffices where daily arrivals once barely met demand,” a clear indication of the Landing’s diminishing commercial importance.

Population decline followed these economic shifts. The Sentinel reported in January 1896 that “no fewer than twenty families have departed for Yuma or points beyond in recent months, seeking opportunity where commercial activity remains robust.” This exodus accelerated through the late 1890s, with particular impact on service businesses that relied on a critical mass of residents. School enrollment dropped from approximately 60 students in 1890 to fewer than 20 by 1898, leading to the consolidation of all grades into a single classroom.

The community’s commercial establishment contracted steadily during this period. Tax records indicate that fifteen businesses closed between 1895 and 1900, including two of the three general stores, several saloons, and most specialized services. The Colorado River Journal itself ceased publication in 1897, leaving only the reduced Sentinel to chronicle the community’s diminishing circumstances.

Unlike some declining communities that found alternative economic functions, Castle Dome Landing struggled to identify a new purpose as both mining and river transportation diminished. Brief attempts to promote agriculture in the river bottomlands proved impractical due to unpredictable flooding and limited irrigation technology. Tourism, which would later become important to the region, remained undeveloped as transportation infrastructure focused on more accessible locations.

The final chapter came with surprising swiftness. In 1903, the larger mining operations in the Castle Dome district consolidated under new ownership that chose to ship exclusively via the now-completed rail connection, bypassing the Landing entirely. The following year, regular steamboat service to the Landing ceased, with vessels continuing to operate only to more isolated communities farther up the Colorado. The Castle Dome Sentinel published its final edition in June 1904 before relocating to Yuma, noting simply: “With commercial operations now centered elsewhere and population reduced to fewer than 200 souls, this publication concludes its service to the Landing community.”

By 1910, census records indicate fewer than 50 residents remained, mostly engaged in small-scale prospecting or subsistence activities. The post office closed officially in 1907, though mail had been delivered only irregularly for several years prior. Many buildings were dismantled for lumber and other reusable materials, accelerating the physical erasure of the town.

A small cluster of determined residents maintained a presence until around 1920, primarily older individuals with deep attachment to the location. The last known year-round resident, James Harvell (a former steamboat pilot), reportedly left in 1922 after a flood damaged his home beyond practical repair. After his departure, the site returned primarily to natural desert conditions, with occasional use by transient prospectors or cattle operations in the surrounding range.

Castle Dome Landing occupies a distinctive place in Arizona’s territorial history as both a transportation hub and mining service community that flourished before railroads redefined the region’s development patterns. The settlement represents an important chapter in the Colorado River’s commercial history, when steamboats connected the isolated Southwest to California markets and eastern goods.

Historically, Castle Dome Landing served as a vital link in the mineral extraction economy that drove much of Arizona’s early development. The silver and lead from the Castle Dome Mining District contributed significantly to territorial growth, providing both direct employment and tax revenue that supported broader infrastructure development. Historical records suggest the district produced approximately $7 million in silver and lead (in 19th-century values) during its operational period—wealth that circulated throughout the territory.

The Landing’s development paralleled Arizona’s transition from military outpost to mining region to more diversified economy. Its rise and fall exemplify the boom-and-bust cycle that characterized many Western resource communities, though its transportation function gave it greater longevity than some purely extractive settlements. The community’s fifteen-year decline offers particularly valuable insights into how frontier settlements adapted to changing economic circumstances, sometimes successfully prolonging their existence and sometimes failing to find new purpose.

For Quechan (Yuma) and other Native American peoples whose traditional territories encompassed the Castle Dome area, the mining settlement represented a complex historical intersection. Documentary evidence indicates both conflict and cooperation between indigenous communities and Landing residents. Archaeological evidence suggests some economic exchange occurred, with Native American pottery and crafts found among Landing artifacts indicating trade relationships. The Colorado River Journal occasionally reported on interactions with native communities, though typically from a settler perspective that privileged mining and transportation interests over indigenous claims.

The Landing’s multicultural character reflected broader patterns of diverse settlement throughout the Southwest borderlands. Census records and business directories document Mexican, Chinese, European, and Anglo-American residents creating a community more varied than many simplified frontier narratives suggest. This diversity manifested in multiple languages spoken, varied religious practices, and cultural exchanges visible in everything from food ways to construction techniques in surviving structures.

Contemporary scholars value Castle Dome Landing as a case study in borderlands history, where national identities remained fluid well after formal boundaries were established. The community maintained connections with Mexican settlements across the Colorado, creating economic and cultural links that transcended the international boundary. Chinese residents maintained trading networks stretching to California and beyond, integrating the seemingly isolated outpost into transpacific commercial systems.

The site’s archaeological significance was formally recognized in 1980 when the Castle Dome Landing Archaeological District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This designation acknowledges both the settlement’s historical importance and the research potential of its remaining material evidence. Controlled archaeological surveys have documented over 200 features across the 30-acre townsite, including building foundations, industrial areas, trash middens, and evidence of riverboat docking facilities.

Today, while the physical site of Castle Dome Landing remains largely inaccessible on military land, its historical significance is preserved and interpreted through the Castle Dome Mine Museum. This facility, located near the former mining town rather than the Landing itself, maintains artifacts, photographs, and documents relating to both settlements. The museum’s preservation work ensures that the Landing’s story remains part of public understanding of Arizona’s development, connecting visitors to this vanished river port and the economic networks it supported.

The contrasting fates of Castle Dome Landing’s two cemeteries illustrate broader patterns in how communities remember their dead and how physical memorials persist or fade with time. Both burial grounds suffered decades of neglect following the town’s abandonment, but recent preservation efforts have taken different approaches to each site based on physical condition, accessibility, and documentation.

The pioneer cemetery, located closer to the river on relatively unstable ground, has experienced greater natural deterioration. Periodic flooding, despite its elevated position, has damaged or displaced many markers. Its location on what is now military land has complicated preservation efforts, limiting regular access for documentation and maintenance. Archaeological work in the 1990s primarily focused on recording what remained rather than restoration, producing detailed maps, photographs, and descriptions of surviving markers and grave features.

In 2003, a limited stabilization project received special permission from military authorities, allowing a team from the Arizona Pioneer Cemetery Research Project to install simple protective barriers around the most vulnerable remaining graves. This minimally invasive approach acknowledged both the site’s sensitive archaeological status and the military’s legitimate concerns about ongoing access to active training areas. The project documented 28 still-identifiable graves, though ground-penetrating radar suggested at least 40 burials remain.

The community cemetery, located on slightly higher ground outside current military boundaries, has received more extensive preservation attention. Beginning in 2005, the Yuma County Historical Society undertook a multi-year documentation and stabilization project that recorded all visible markers, repaired damaged monuments where possible, cleared invasive vegetation, and installed a perimeter fence marking the cemetery boundaries.

This work identified 114 marked graves with legible information and approximately 30 additional unmarked burials. Conservation philosophy emphasized preservation rather than restoration, stabilizing damaged markers in their weathered state rather than attempting to return them to original condition. This approach maintains the cemetery’s authentic character while preventing further deterioration.

Family connections to both cemeteries have proven surprisingly durable despite the passage of time. Descendants of several Landing families, now scattered throughout Arizona and California, participated in the community cemetery preservation project, providing photographs, letters, and oral histories that enriched understanding of those buried there. These family materials sometimes corrected or expanded information from weathered markers, reconnecting names with personal stories and community roles.

Memorial practices have evolved from abandonment to rediscovery. Following the Landing’s decline, occasional family members made isolated visits to graves, but organized remembrance largely ceased by the 1930s. The modern rediscovery of these burial grounds has sparked new commemorative traditions. Since 2010, an annual memorial service has been held at the community cemetery each November, bringing together historians, military representatives, descendants, and interested public to honor those buried there.

This contemporary memorial practice intentionally incorporates elements from the various cultural traditions represented in the cemetery. Catholic, Protestant, Native American, and Chinese remembrance customs are acknowledged, creating an inclusive ceremony that recognizes the community’s diverse heritage. These events serve both commemorative and educational purposes, connecting visitors to the multicultural reality of Arizona’s territorial development.

The cemeteries’ preservation faces ongoing challenges from both natural and human factors. The harsh desert environment continues to weather markers, while potential changes to military land use could affect access to the pioneer cemetery. Limited funding for maintenance presents persistent concerns, with preservation work largely dependent on volunteer efforts and occasional grants rather than sustainable institutional support.

Digital preservation has emerged as an important complement to physical conservation. Both cemeteries have been comprehensively photographed, with images and transcriptions available through the Arizona Memory Project online database. This digital access ensures that even if physical markers eventually succumb to time and elements, the information they contain remains accessible to researchers, descendants, and the interested public.

While Castle Dome Landing itself remains largely inaccessible due to its location on active military land, visitors interested in connecting with this historical community have several options that balance accessibility with respect for both the site’s historical significance and current land use realities.

The primary point of connection for most visitors is the Castle Dome Mine Museum, located approximately 15 miles east of the original Landing site. This open-air museum preserves and interprets the mining community that the Landing once served, with over 50 restored and reconstructed buildings creating an immersive historical environment. While not the Landing itself, this site maintains the most comprehensive collection of artifacts, photographs, and documents relating to both the mines and the river port that supported them.

The museum’s visitor center includes a dedicated exhibit on Castle Dome Landing, featuring scale models of the settlement, steamboats, and docking facilities based on archaeological evidence and historical photographs. Interactive displays explain the vital connection between river transportation and mining operations, helping visitors understand why the Landing developed where it did and how changing transportation patterns contributed to its decline.

For those specifically interested in the cemeteries, the community cemetery is accessible through a guided tour program operated monthly by the Yuma County Historical Society. These tours, conducted by trained volunteers, provide historical context for the burial ground while emphasizing respectful visitation practices. Visitors are asked to remain on designated paths, refrain from touching fragile markers, and never remove items from the site, regardless of how insignificant they might appear.

Photography is permitted at the community cemetery for personal and educational use, though commercial photography requires special permission from the historical society. Visitors are encouraged to share their photographs with the society’s digital archive project, which seeks to document changes to the cemetery over time and identify previously unrecorded features or inscriptions.

The pioneer cemetery remains largely inaccessible to the general public due to its location on military land. Occasional controlled access is permitted for qualified researchers and preservation specialists through an application process with both the Yuma Proving Ground authorities and the Arizona State Historic Preservation Office. These restrictions, while limiting public engagement, have actually helped protect the site from vandalism and unauthorized collection activities that have damaged many accessible ghost town cemeteries.

For those unable to visit in person, virtual tours of both cemeteries are available through the Arizona Heritage Project website, featuring 360-degree panoramic photography, detailed marker transcriptions, and oral histories from descendants. This digital access represents an important compromise between preservation concerns and public interest in connecting with these historical sites.

Both cemeteries face preservation challenges specific to their desert environment. Extreme heat, occasional flash flooding, and shifting sands all threaten the physical integrity of remaining markers. Visitors to the community cemetery should be prepared for harsh conditions, carrying adequate water and sun protection, and should visit only during cooler morning hours during summer months.

For those seeking deeper engagement with Castle Dome Landing’s history, research resources are available through several institutions. The Yuma Territorial Prison State Historic Park maintains archives of both newspapers, along with business records, photographs, and personal correspondence from Landing residents. The Arizona Historical Society in Tucson holds additional materials, including steamboat company records and mining company documents that illuminate the economic foundations of the community.

As the sun sets over the empty desert where Castle Dome Landing once thrived, casting long shadows from the weathered grave markers of its cemeteries, we are reminded of the ephemeral nature of human endeavor. A town that once rivaled Yuma in size and significance has returned to the desert, leaving behind only scattered foundations, fading newspaper accounts, and the silent testimony of those who rest in its cemetery grounds.

Yet in this seeming emptiness, Castle Dome Landing speaks eloquently about the cycles of Western American development—the rush of mineral discovery, the vital importance of transportation networks, the building of multicultural community, and the eventual reconciliation with economic and environmental realities. The settlement’s rise and fall paralleled Arizona’s territorial development, reflecting broader patterns of frontier exploitation, community building, and eventual transformation or abandonment.

The pioneers who rest in Castle Dome Landing’s cemeteries came seeking opportunity on a distant frontier but created something more lasting in the process—they helped establish the economic and social foundations of modern Arizona. Their newspapers documented not just local happenings but the broader patterns of territorial development. Their riverboat connections integrated this remote outpost into national and international networks of commerce and communication before changing transportation technology rendered their location obsolete.

What endures beyond production statistics and population figures is the human story of adaptation, community-building, and perseverance in an unforgiving landscape. Captain Blackmar’s steamboat expertise, Elena Torres’ educational leadership, and Lee Wong’s entrepreneurial persistence represent different facets of the complex society that briefly flourished here—one built not just on mineral extraction and transportation but on the full range of human creativity and connection.

The cemetery markers, newspaper accounts, and archaeological remains collectively tell a story more nuanced than simple boom-and-bust. They reveal a community that, for a time, transcended the limitations of its isolated location to create meaningful lives and lasting institutions. The multicultural character of Castle Dome Landing—visible in its burial grounds, documented in its newspapers, and evident in archaeological remains—reminds us that Arizona’s development involved diverse peoples whose contributions sometimes fade from simplified historical narratives.

As contemporary Arizona addresses questions of sustainable development, transportation infrastructure, and economic diversification, Castle Dome Landing offers valuable perspective on both change and continuity in human relationships with the challenging desert landscape. The ghost town stands as neither cautionary tale nor romantic vision, but rather as a nuanced chapter in the ongoing story of human adaptation to the American Southwest—a place where pioneer dreams rest but continue to inform our understanding of both past and future possibilities in this remarkable region.

Arizona Historical Society. (1980). Castle Dome Landing and Mining District: Historical Records Collection. Tucson, AZ.

Granger, T. (1874-1904). Collected Editions of the Castle Dome Sentinel. Arizona State Archives.

Johnson, M. (1998). Colorado River Ports: Ehrenberg, Castle Dome, and Yuma. Yuma: Territorial Press.

Rheinhart, J. (1868-1897). Collected Editions of the Colorado River Journal. Yuma Territorial Prison Archives.

Wilkinson, F. (1988). Steamboats on the Colorado River, 1852-1916. University of Arizona Press.

Castle Dome Mine Museum

Primary site for artifacts and information about the mining district and Landing

Yuma Territorial Prison State Historic Park

Contains archives related to Castle Dome Landing

Arizona Historical Society, Tucson

Houses steamboat company records and mining documents

Yuma County Historical Society

Maintains cemetery records and conducts preservation projects

Castle Dome Mine Museum is located approximately 55 miles north of Yuma, Arizona

Site is accessible via Castle Dome Road off Highway 95

GPS coordinates: 33°02′45″N 114°11′20″W

Museum hours: 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM October through April, closed during summer months

Community Cemetery tour information available through Yuma County Historical Society

Historic photographs courtesy of the Yuma Territorial Prison State Historic Park Collection

Cemetery documentation photos by Arizona Pioneer Cemetery Research Project

Artifact photography by Castle Dome Mine Museum

Contemporary site photography by Yuma County Historical Society

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By using our site, you consent to cookies.

Manage your cookie preferences below:

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.