The sun-bleached ruins scattered across Arizona’s landscape tell stories of ambition, prosperity, and ultimate abandonment. From the towering mountains of the north to the searing deserts of the south, Arizona’s ghost towns stand as compelling monuments to the boom-and-bust cycles that defined the American West. These forgotten communities—once vibrant centers of mining, commerce, and frontier life—emerged rapidly between the 1860s and early 1900s as prospectors discovered rich deposits of silver, gold, and copper throughout the territory.

What began with individual prospectors swinging pickaxes soon transformed into industrial operations with stamp mills, smelters, and shaft mines that employed hundreds. Towns appeared virtually overnight, complete with saloons, hotels, and opera houses. Some settlements flourished for decades, while others burned brightly for just a few years before economic forces, declining ore quality, or natural disasters sealed their fate.

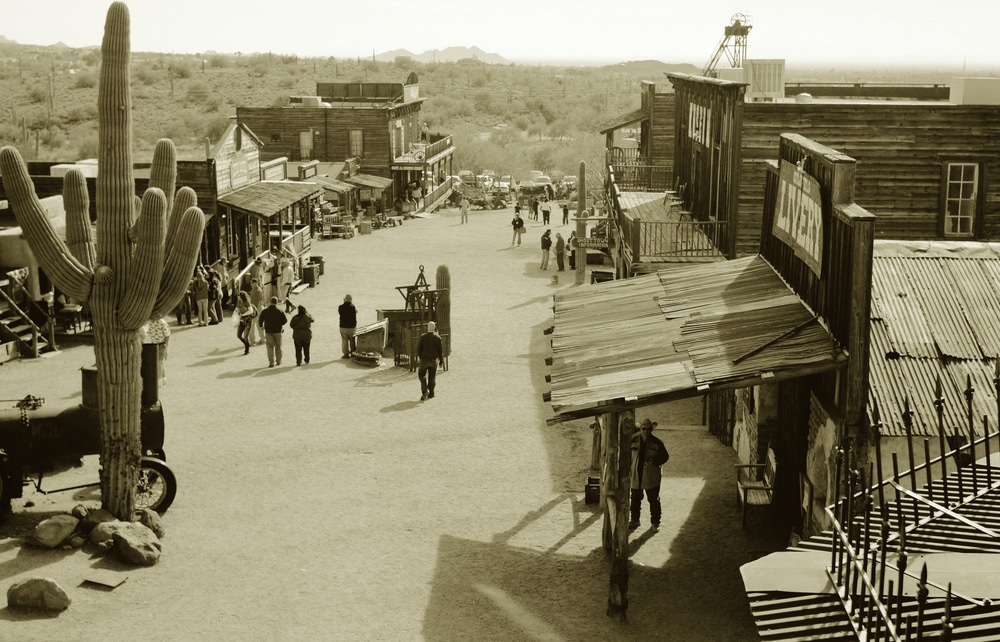

Today, these abandoned settlements exist on a spectrum of preservation. Some, like Jerome and Tombstone, have reinvented themselves as tourist destinations where visitors can walk historic streets and enter preserved buildings. Others remain as authentic ruins—crumbling adobe walls, weathered wooden structures, and silent mine shafts reclaimed by the desert. Many exist only as scattered foundations, cemetery plots, or mere mentions in territorial records.

These ghost towns serve as tangible connections to Arizona’s territorial period (1863-1912), offering glimpses into the lives of miners, merchants, families, and outlaws who shaped the state’s identity. Each abandoned building, rusty piece of mining equipment, and weathered gravestone provides a window into Arizona’s pivotal role in America’s western expansion and industrial development.

The story of Arizona’s ghost towns is inseparably tied to the mineral wealth hidden beneath its rugged terrain. The territory’s first significant mineral rush began after the 1858 Gadsden Purchase secured the southern portion of Arizona from Mexico. Prospectors soon discovered substantial silver deposits in places like Tombstone, creating one of the richest silver districts in American history.

While silver dominated southern Arizona, gold fever swept the central and northern mountains. Mining camps like Goldfield, Oatman, and Wickenburg emerged as prospectors extracted placer gold from streambeds before developing hard rock mines. By the 1880s, copper became Arizona’s dominant mineral, transforming small operations into industrial behemoths that built company towns like Jerome, Bisbee, and Clifton.

The arrival of railroads proved decisive in town survival. Communities located near the Southern Pacific or Santa Fe railroad lines thrived with reliable transportation for ore shipments and supplies. Those in remote canyons or distant mesas faced higher operating costs and eventual abandonment. Similarly, access to water determined which settlements could sustain themselves in Arizona’s arid environment, with towns near rivers having distinct advantages over those dependent on hauled water.

As ore quality declined and mineral prices fluctuated, the economic foundation of these communities crumbled. The 1893 silver crash devastated mining camps throughout Arizona, while later waves of abandonment followed economic downturns, fires, floods, and eventually, World War II production restrictions. What remains today tells the story of Arizona’s early economic development and the transient nature of resource-based communities.

Daily life in Arizona’s mining communities balanced harsh realities with frontier resilience. Miners descended into the earth for grueling shifts, working by candlelight in dangerous conditions for $3-4 per day. Above ground, communities developed complex social structures that transcended the simple “Wild West” mythology.

These towns were remarkably diverse. Mexican miners brought generations of expertise, Chinese merchants established businesses, European immigrants applied Old World mining techniques, and Eastern Americans brought capital and industrial approaches. Many communities featured distinct ethnic neighborhoods with their own cultural institutions.

Despite their remote locations, these towns often developed surprisingly sophisticated amenities. Larger settlements boasted opera houses, breweries, newspapers, and schools. Saloons served as community centers where miners could find entertainment, information, and brief escape from difficult conditions. Churches established missions to civilize what they considered the untamed frontier, while women created cultural societies and organized community improvements.

Life remained challenging by modern standards. Summer heat, winter isolation, disease outbreaks, and mining accidents created constant hardship. Water often had to be hauled for miles, wood for heating and cooking became scarce as forests were harvested, and fresh food was a luxury in many remote locations. Yet historical accounts reveal communities filled with determination, entrepreneurial spirit, and the belief that prosperity waited just below the next layer of rock.

The ghost towns that dot Arizona’s landscape today exist in various states of preservation, facing different challenges in their ongoing battle against time and the elements.

Restored Destinations like Jerome, Tombstone, and Goldfield represent communities that have embraced their ghost town identity, restoring historic buildings and creating tourism-focused economies. These locations offer the most accessible ghost town experience, with museums, guided tours, and interpretive displays that explain their historical significance. While offering excellent educational value, these sites sometimes balance historical authenticity with commercial interests.

Partially Preserved Sites like Ruby, Fairbank, and Vulture Mine maintain significant original structures with minimal restoration, providing a more authentic experience of abandonment. These locations often operate under limited hours with basic facilities, preserving their historical integrity while allowing controlled access. Many are managed by historical societies, government agencies, or private owners committed to preservation without commercialization.

Endangered Ruins like Courtland, Swansea, and Harshaw face significant threats from weathering, vandalism, and neglect. These fragile sites offer the most authentic experience but require visitors to practice strict preservation ethics. Many exist on public lands with minimal oversight, making visitor responsibility essential to their survival.

Preservation challenges are considerable. Private ownership of ghost town sites sometimes restricts access or leads to inappropriate development, while public land management agencies struggle with limited funding for stabilization projects. Climate change intensifies weather patterns that accelerate deterioration, and increasing visitation brings both awareness and impact to fragile structures.

Arizona’s ghost towns aren’t just about abandoned buildings—they’re settings for remarkable human stories that blur the line between documented history and frontier mythology.

In Tombstone, the legendary 1881 Gunfight at the O.K. Corral between the Earp brothers and the Clanton-McLaury faction lasted just 30 seconds but defined the town’s identity for over a century. Less famous but equally fascinating is the story of Nellie Cashman, the “Angel of Tombstone,” who operated restaurants and boarding houses while organizing charitable efforts throughout Arizona’s mining districts.

The lost Jacob Waltz “Lost Dutchman” gold mine near Phoenix has spawned one of the Southwest’s most enduring mysteries, with the alleged rich gold deposit remaining undiscovered despite generations of searchers combing the Superstition Mountains. Each year, prospectors still vanish in pursuit of this elusive treasure.

Jerome earned its reputation as the “Wickedest Town in the West” with its notorious red-light district called “Husband’s Alley” and the violent labor conflicts between miners and companies. Meanwhile, Oatman claims generations of visitors have witnessed the ghost of “Oatie” the miner wandering the halls of its historic hotel.

Whether documented fact or colorful exaggeration, these stories reveal how ghost towns have been mythologized in ways that capture the public imagination while sometimes obscuring the more complex historical realities of these communities.

Jerome (Yavapai County) perches dramatically on Cleopatra Hill overlooking the Verde Valley. Once known as the “Billion Dollar Copper Camp,” this former mining giant produced over 3 million pounds of copper monthly at its peak. After near-total abandonment in the 1950s, Jerome reinvented itself as an arts community and tourism destination. Visitors can explore the Douglas Mansion State Historic Park, wander preserved downtown streets, and stay in historic hotels reportedly haunted by mining-era spirits.

Tombstone (Cochise County) earned its nickname as “The Town Too Tough to Die” by surviving both mining decline and devastating fires. The site of the famous 1881 O.K. Corral gunfight now features daily reenactments, preserved buildings including the Bird Cage Theatre, and the iconic Boot Hill Cemetery with its colorful epitaphs. Unlike many ghost towns, Tombstone maintains its original street grid and numerous authentic structures.

Goldfield (Pinal County) near the Superstition Mountains flourished briefly in the 1890s before its gold deposits played out. Today’s reconstructed mining town offers underground mine tours, gunfight shows, and period demonstrations. While more commercialized than some sites, it provides family-friendly access to Arizona’s mining heritage and connections to the Lost Dutchman legend. The town’s strategic location near the mysterious Superstition Mountains enhances its appeal, with comprehensive historical exhibits that document the area’s gold mining operations and frontier development.

Oatman (Mohave County) on historic Route 66 welcomes visitors with wild burros descended from miners’ abandoned pack animals. This former $10 million gold producer maintains its weathered wooden buildings, including the Oatman Hotel where Clark Gable and Carole Lombard reportedly spent their honeymoon. The town balances preservation with tourism through regularly scheduled staged gunfights that recreate Old West conflicts, offering an entertaining glimpse into frontier justice while maintaining its authentic mining-era character.

Ruby (Santa Cruz County) offers Arizona’s most intact ghost town experience on private property near the Mexican border. This remarkably preserved former mining town features a collection of original structures including a schoolhouse, jail, and various mining buildings surrounding a picturesque lake. The site has avoided the commercialization that characterizes more tourist-oriented ghost towns, maintaining its authentic early 20th century atmosphere. The private ownership ensures careful preservation while guided tours provide access to this remote and historically significant location. Ruby’s isolation near the international border contributes to both its pristine condition and the sense of stepping back in time as visitors explore this well-preserved mining community.

Vulture City (Maricopa County) outside Wickenburg features impressive ruins of Arizona’s most productive gold mine, which yielded over $200 million in precious metals. Founded in 1863 by Henry Wickenburg after his discovery of a quartz outcropping containing gold, this once-thriving settlement now showcases carefully restored buildings alongside original structures. The assay office, Wickenburg’s cabin, and the hanging tree where 18 gold thieves reportedly met their end remain visible. The privately owned site offers scheduled tours that balance preservation with education, allowing visitors to explore this significant piece of Arizona mining history.

Fairbank (Cochise County) along the San Pedro River served as an important transportation hub for Tombstone’s mines. Once the bustling heart of the region’s transportation network, Fairbank’s strategic location made it crucial for the success of nearby mining operations. This National Conservation Area site managed by the Bureau of Land Management features a meticulously preserved schoolhouse that now serves as a museum, commercial building foundations that reveal the town’s layout, and an interpretive walking trail connecting to nearby mill sites and the Grand Central Mill. The well-maintained grounds and interpretive signage make Fairbank an excellent introduction to southern Arizona’s mining history.

Swansea (La Paz County) contains substantial ruins of a copper mining operation including smelter remains, miners’ cabins, and the company store foundation. This BLM-protected site requires high-clearance vehicles but rewards visitors with one of Arizona’s most extensive and atmospheric ghost town experiences.

Crown King (Yavapai County) high in the Bradshaw Mountains requires a challenging drive but offers both historic structures and an operating saloon where visitors can encounter both local residents and mining history. The surrounding forest contains numerous mining remnants from the area’s gold boom.

Gleeson, Courtland, and Pearce (Cochise County) form the “Ghost Town Trail” with varying levels of preservation. Gleeson, originally called Turquoise for its valuable mineral deposits, features a restored jail that now serves as a museum chronicling the town’s copper mining past. Courtland, established in 1909 during a copper boom, contains fascinating adobe ruins, the remains of the jail, and a haunting cemetery. Pearce, founded in 1896 following the discovery of rich gold and silver deposits, showcases the impressive Pearce General Store and historic post office buildings that stand as testaments to its former prosperity. These three communities, located within a short drive of each other, offer visitors a comprehensive look at the boom-and-bust cycle of southern Arizona mining settlements.

Helvetia (Pima County) was founded in 1891 as a copper mining town and now features fascinating remnants of its industrial past. Visitors can explore the substantial ruins of the smelter operation and other mining structures that once processed copper ore from the surrounding mountains. The site requires some hiking to fully appreciate but offers a rewarding experience for those interested in Arizona’s mining technology and industrial archaeology.

Johnson (Cochise County) consists of a handful of weathered structures set against the dramatic desert landscape of southeastern Arizona. This former mining community offers visitors the chance to explore a less-visited site with minimal development or tourist infrastructure, creating an authentic experience of discovery.

McCabe (Yavapai County) dates to the late 1800s gold mining era and now features the ruins of its once-productive mill and scattered mining structures. The site’s relative obscurity has helped preserve its authentic character, making it an interesting destination for ghost town enthusiasts looking beyond the more popular destinations.

Harshaw (Santa Cruz County) hides at the end of a rugged forest road with stone foundations, a cemetery with Victorian markers, and the James Finley House chimney. This once-thriving silver mining town now consists primarily of weathered adobe ruins that blend into the landscape and a remarkably preserved cemetery with ornate markers. Harshaw’s remote location has protected it from vandalism and excessive visitation, creating one of Arizona’s most atmospheric abandoned sites. The town’s history as a significant silver producer is evident in the scattered remains of processing facilities and the substantial foundations that hint at its former importance in the region’s mining economy.

Sasco (Pinal County) contains massive concrete foundations of a smelter operation that processed ore from nearby Silver Bell. These industrial ruins create a stark desert monument requiring significant hiking to access fully, with minimal interpretation but powerful visual impact.

Charleston (Cochise County) was established in 1879 as a milling town for Tombstone’s silver operations. Located along the San Pedro River where water was available to power the stamp mills, Charleston once rivaled Tombstone in size and importance. Today, it has been reduced to scattered foundations and a cemetery. Archaeological work has mapped this once-substantial community, though little remains visible above ground.

Signal (Mohave County) represents one of Arizona’s most remote ghost towns, requiring serious backcountry travel to reach scattered mine structures and cabin foundations in the Signal Mountains. The reward for this difficult access is experiencing a site rarely visited since its 1880s heyday.

Dos Cabezas (Cochise County) takes its name from the distinctive twin peaks that loom over this former mining settlement. Located in the rugged mountains of southeastern Arizona, this remote site features a handful of surviving structures including the historic post office. The town’s isolation and challenging access have helped preserve its authentic character while limiting visitor impact.

Paradise (Cochise County) nestles in the Chiricahua Mountains with a few remaining buildings set against a backdrop of dramatic mountain scenery. Once a thriving mining community, Paradise now offers a truly remote ghost town experience for those willing to navigate the difficult forest roads to reach it.

Arizona’s pioneer cemeteries offer some of the most poignant connections to ghost town histories, with weathered markers revealing the harsh realities of frontier life and the diverse communities who built these settlements.

Boothill Cemetery (Tombstone) stands as Arizona’s most famous burial ground, with graves of the McLaury brothers and Billy Clanton from the O.K. Corral gunfight alongside markers with evocative epitaphs like “Here lies Lester Moore, Four slugs from a 44, No Les No More.” The cemetery’s name reflects the reality that many occupants died “with their boots on” through violence or accident.

Pioneer and Military Memorial Park (Phoenix) encompasses seven historic cemeteries established in 1884, including specialized sections for the Ancient Order of United Workmen and Knights of Pythias fraternal organizations. Notable interments include Darrell Duppa, the English-born pioneer credited with naming Phoenix, and Jacob Waltz, the mysterious prospector associated with the legendary “Lost Dutchman Mine” in the Superstition Mountains.

Harshaw Cemetery (Santa Cruz County) contains ornate Victorian markers with poetic inscriptions alongside simple wooden crosses, reflecting the economic and cultural divides within mining communities. The remote hillside location offers contemplative views across landscapes that appear little changed since the mining era.

Gleeson Cemetery (Cochise County) features sections segregated by ethnicity, religion, and economic status—a physical manifestation of the social structures that defined these communities. Chinese, Mexican, European, and American graves demonstrate the international nature of Arizona’s mining rushes.

Jerome Cemetery (Yavapai County) climbs the steep mountainside in distinct sections for different ethnic and religious groups, with dramatic views of the Verde Valley below. The terraced arrangement and variety of markers create one of Arizona’s most visually compelling historic burial grounds.

Hardyville Pioneer Cemetery (Bullhead City) serves as the only surviving remnant of Hardyville, a once-thriving shipping port established in 1864 on the Colorado River. While the town itself has virtually disappeared, this cemetery established around 1867 provides tangible evidence of the settlement’s existence and importance to early transportation networks in the region.

Arizona Pioneers’ Home Cemetery (Prescott) contains sections dating back to the 1800s and serves as the final resting place for many of Arizona’s territorial pioneers. The cemetery is managed by the historic Arizona Pioneers’ Home, which was established in 1910 as a state-funded retirement home for early settlers who helped build the state.

Henry Wickenburg Pioneer Cemetery (Wickenburg) honors the founder of Vulture Mine and the town that bears his name. Established in 1902, this historic burial ground is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and contains graves of many early residents who shaped the development of this important mining and ranching community.

These cemeteries require particular visitor respect. Photography should avoid disturbing grave items or disrespecting cultural sensitivities. Many sites have ongoing family connections with descendants still placing flowers and maintaining markers. Walking paths should be strictly followed, and no physical contact with historic markers is appropriate given their fragility.

Exploring Arizona’s ghost towns demands both preparation and ethical responsibility. These fragile historic sites face increasing visitation pressure, making preservation awareness essential for their survival.

Photography is welcome at most locations, but commercial photography may require permits. Drone usage is prohibited at most preserved sites and requires special permission from land management agencies at others.

Many ghost towns offer guided experiences that combine historical expertise with responsible access:

Arizona’s ghost towns represent irreplaceable windows into the state’s formative period—a time when settlements rose and fell with the fortunes of mineral extraction. From the well-preserved streets of Jerome and Tombstone to the vanishing traces of Bradshaw City and Contention, these sites collectively tell the story of Arizona’s transition from rugged territory to modern state.

The weathered buildings, rusty machinery, and silent cemeteries offer more than mere curiosity—they provide tangible connections to the diverse communities that shaped Arizona’s cultural identity. Through responsible visitation and preservation advocacy, we can ensure these historical treasures remain for future generations to explore and understand.

As you journey deeper into specific ghost town histories through our individual site pages, remember that each crumbling adobe wall and weathered wooden structure represents both a community’s dreams and the resilience of structures standing against time and elements. Your respectful exploration helps write the next chapter in these sites’ ongoing stories.

We invite you to discover Arizona’s ghost towns through our detailed guides, contribute to preservation efforts through historical societies and conservation organizations, and share your experiences with others who appreciate these fragile windows into our shared past.

| Ghost Town | Location | Est./Abandoned | History | Remnants | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jerome | Yavapai County | 1876/Semi-abandoned 1950s | Once “Wickedest Town in the West,” thriving copper mining hub that peaked at 15,000 residents | Well-preserved buildings, now an arts community with ~450 residents | Fully accessible, popular tourist destination |

| Goldfield | East of Phoenix | 1892/1898 (revived 1921-1926) | Gold mining boomtown that produced $3 million in ore | Reconstructed as tourist attraction with period buildings | Open to public with admission fee |

| Ruby | Santa Cruz County | 1870s/1940s | Mining town known for rich lead, zinc, copper, silver deposits and notorious double murders | One of best-preserved ghost towns with intact buildings | Private property, fee for access (limited hours) |

| Vulture City | Near Wickenburg | 1863/1942 | Founded after discovery of Vulture Mine, Arizona’s most productive gold mine | 12+ restored structures including assay office, brothel, and school | Recently reopened for tours |

| Tombstone | Cochise County | 1879/Not fully abandoned | Famous for O.K. Corral gunfight, silver mining boomtown | Historic district preserved as “The Town Too Tough to Die” | Active tourist town with preserved historic area |

| Oatman | Mohave County | 1908/Semi-abandoned 1960s | Gold mining boom town named after Olive Oatman | Historic buildings, wild burros roaming streets | Active tourist destination on Route 66 |

| Chloride | Mohave County | 1863/Semi-abandoned 1940s | Silver mining town, Arizona’s oldest continuously inhabited mining town | Historic buildings, murals by Roy Purcell | Accessible with some residents, gift shops |

| Crown King | Bradshaw Mountains | 1875/Semi-abandoned | Gold mining town accessible by treacherous mountain road | General store, saloon, some original buildings | Remote but accessible, popular for off-roading |

| Swansea | La Paz County | 1908/1937 | Copper mining town named after Swansea, Wales | Stone foundations, smelter ruins, cemetery | Remote BLM land, accessible by 4WD vehicles |

| Gleeson | Cochise County | 1900/1940s | Copper, lead and silver mining town | Jail, cemetery, ruins of hospital and store | Mostly private property, limited access |

| Fairbank | Cochise County | 1881/1970s | Important transportation hub and rail depot for Tombstone | Schoolhouse (visitor center), commercial building ruins | San Pedro Riparian Conservation Area, freely accessible |

| Pearce | Cochise County | 1894/1940s | Gold and silver mining town founded by Cornish miner James Pearce | General store, post office, cemetery | Partially accessible, some private property |

| Contention City | Cochise County | 1879/1888 | Mill town and transportation point for Tombstone silver | Almost nothing remains | Site can be visited but few visible remains |

| Congress | Yavapai County | 1884/1930s | Gold mining town where workman “Diamond Jack” found his fortune | Mine ruins, cemetery | Partially accessible, some private property |

| Castle Dome | Yuma County | 1863/1979 | Lead and silver mining hub | Reconstructed as museum with 50 buildings | Castle Dome Mine Museum open to public |

| Dos Cabezas | Cochise County | 1878/1960s | Gold mining town named for twin peaks resembling “two heads” | Adobe ruins, foundations | Mostly private property |

| Harshaw | Santa Cruz County | 1877/1930s | Silver mining town named for David Harshaw | Cemetery, ruins of buildings | Some access, partially private property |

| Bumble Bee | Yavapai County | 1863/1930s | Stage stop, then mining supply town | Few restored buildings | Visible from Bumble Bee Road |

| Total Wreck | Pima County | 1883/1890s | Silver mining town named after investor’s comment on the claim | Scattered ruins, mine shafts | Remote access on private and public lands |

| Courtland | Cochise County | 1909/1920s | Copper mining boomtown that grew to 2,000 residents | Jail, ruins of buildings, cemetery | Free access on dirt roads |