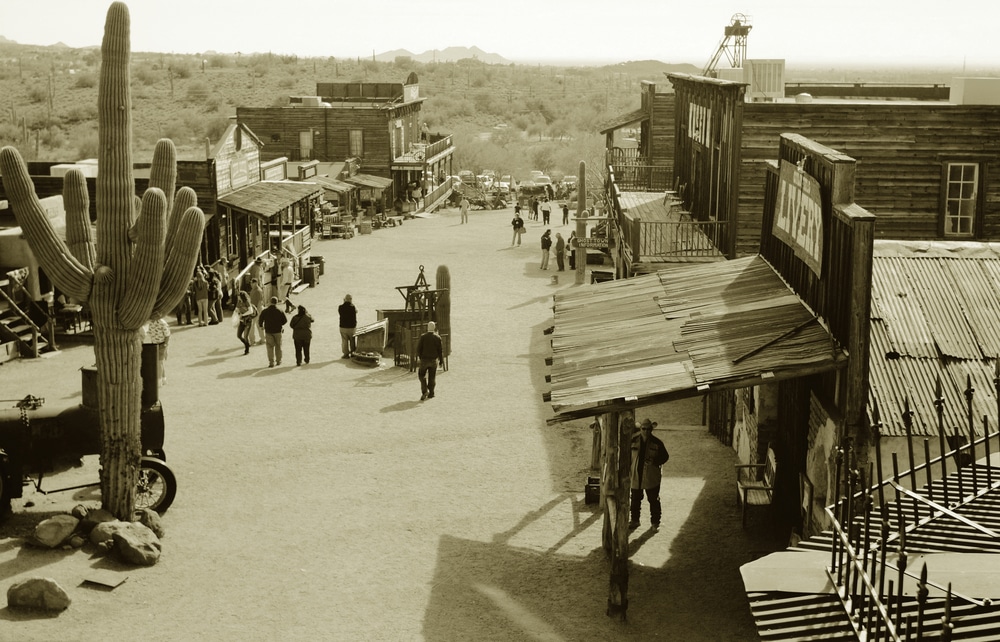

The afternoon sun casts long shadows across weathered wooden boardwalks and faded storefronts that line the dusty main street of what was once one of Arizona’s most promising mining settlements. Here, beneath the watchful gaze of the Superstition Mountains, Goldfield stands as a testament to the fleeting nature of frontier prosperity. The creak of an old wooden sign and the distant call of a red-tailed hawk are the only sounds that break the desert stillness where the bustling noises of 4,000 gold-seekers once filled the air.

Located in what is now Pinal County, just six miles northeast of Apache Junction and a short journey from Phoenix, Goldfield emerged in the early 1890s as a shining example of how quickly fortune could transform the Arizona wilderness into a center of commerce and community. Today, the town’s carefully preserved remains, its pioneer cemetery, the broader community burial grounds, and the echoes of its once-vibrant press and transportation networks tell a compelling story of ambition, hardship, and the impermanence of resource-driven settlements.

As we walk these grounds where dreams were built and ultimately abandoned, the weathered headstones and silent mine shafts reveal fundamental truths about the nature of Arizona’s territorial development—where the promise of mineral wealth could conjure entire communities from the desert floor, only to see them reclaimed by the same unforgiving landscape when the gold veins narrowed and the profits dwindled.

Step into the past as you stroll the wooden boardwalks of Goldfield’s restored streets. The town includes original and reconstructed buildings such as a saloon, blacksmith shop, church, jail, and general store—each packed with character and Old West charm.

Descend into a reconstructed section of the historic Mammoth Gold Mine with a guided tour that explains how miners once lived and worked in the treacherous tunnels. You’ll learn about mining techniques, tools, and the gold rush that put Goldfield on the map.

This 36-inch gauge train takes passengers on a scenic 20-minute ride around the perimeter of the town. Along the way, you’ll get views of the Sonoran Desert, old mining equipment, and hear fun historical narration about Goldfield and the surrounding Superstition Mountains.

Every weekend, Goldfield hosts staged Old West shootouts featuring the Goldfield Gunfighters. These fun, theatrical performances bring the lawless frontier days to life with comedy, drama, and authentic period costumes.

Learn more about the town’s rise and fall during the 1890s gold boom. The museum contains fascinating exhibits on mining, local legends (including the Lost Dutchman Mine), and artifacts from Goldfield’s heyday.

For thrill-seekers, the Superstition Zipline offers a soaring ride over the ghost town with spectacular views of the desert and mountains. It’s a family-friendly adventure that adds a modern twist to the historic setting.

Get your hands dirty with gold panning activities available in the town. It’s a fun, hands-on experience for kids and adults alike, offering a glimpse into the hopes and struggles of prospectors who once searched for riches in these hills.

Just steps from the ghost town, the surrounding landscape offers hiking trails that lead into the rugged beauty of the Superstition Wilderness. Popular routes include the Hieroglyphic Trail and the Lost Dutchman State Park trails.

Goldfield offers a variety of Western-themed shops where you can buy everything from cowboy hats and old-time photos to handcrafted jewelry, Native American art, and desert souvenirs. Don’t miss the blacksmith shop for live demonstrations.

The cemeteries, newspaper accounts, and surviving records of Goldfield preserve fragments of individual stories that breathe life into the town’s history. In the pioneer cemetery, one weathered sandstone marker commemorates Michael O’Rourke, a 35-year-old miner from County Cork, Ireland who, according to an account in the Nugget, arrived in early 1894 “with nothing but experience and determination” only to die six months later in a collapse at the Mammoth Mine. The newspaper reported that his funeral was “attended by nearly every Irishman in the district, who raised funds to ensure their countryman had a proper burial and headstone.”

Another notable grave belongs to Sarah Jenkins, one of the first women to establish a business in Goldfield. Her marker, now partly illegible, identifies her as the “Proprietress of Jenkins Boarding House” who died in March 1895. Historical accounts suggest she arrived in late 1893 and quickly established a reputation for providing clean accommodations and quality meals—a significant comfort in the rough mining camp. The Nugget reported that her funeral procession included “not only the town’s respectable ladies but many miners who had found in her establishment something of the home comforts they had left behind.”

In the community cemetery, the elaborate grave of Heinrich Mueller tells another tale of frontier opportunity. Mueller, a German immigrant and trained assayer, established Goldfield’s first reliable assay office, providing crucial services to both individual prospectors and larger mining operations. When he died of pneumonia in December 1896, the community recognized his contributions with an imported marble headstone featuring German inscriptions and Masonic symbols, reflecting his prominent role in establishing the Goldfield Masonic Lodge.

Family connections emerge in the burial of four members of the Richardson family, whose graves lie side by side in the community cemetery. James Richardson, his wife Elizabeth, and their two young daughters all died within a three-week period in September 1894, victims of the typhoid outbreak that swept through the town. Their tragedy, documented sympathetically in both newspapers, prompted the town council to implement improved sanitation regulations and establish a rudimentary board of health to prevent future epidemics.

The hardships of mining life are further revealed in records of accidents and violence. A report in the Sentinel from August 1895 describes a dispute over claim boundaries that escalated into a shooting at the Golden Eagle Saloon, resulting in the death of prospector William Taylor. His simple grave in the pioneer cemetery bears the inscription “Died defending his rightful claim,” suggesting how property disputes could quickly turn deadly in communities where formal legal structures were still developing.

Personal accounts preserved in letters and newspaper articles speak to the community bonds that formed despite the transient nature of many mining populations. When fire destroyed several businesses in early 1896, the Nugget reported that “citizens rallied with remarkable generosity, ensuring that each affected proprietor received assistance in rebuilding.” Similarly, when the young schoolteacher Margaret Wilson contracted tuberculosis, a benefit dance at the Mammoth Hotel reportedly raised over $300 for her treatment—a substantial sum that demonstrated the value placed on education even in a rough frontier community.

These human stories reveal Goldfield as more than just a site of economic activity but as a community of individuals with hopes, fears, and connections that transcended the purely commercial nature of the town’s existence. The care taken with burials, the charitable responses to misfortune, and the establishment of community institutions all speak to the desire to create something more permanent than a temporary mining camp, even if those aspirations were ultimately unfulfilled.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | Goldfield, Arizona |

| Type | Restored ghost town / living history attraction |

| County | Pinal County |

| Founded | 1893 |

| Status | Reconstructed town with shops, attractions, and tourism |

| Population (Historic) | ~1,500 at peak in the mid-1890s |

| Population (Current) | No residents; operates as a themed tourist town |

| Historical Significance | Founded after gold was discovered near the Superstition Mountains |

| Primary Industry | Gold mining from the Mammoth Mine |

| Post Office | Operated from 1893 to 1897 |

| Decline Factors | Ore vein disappeared; town was abandoned by 1898 |

| Modern Revival | Restored in the 1980s–1990s as a tourist destination |

| Key Attractions | Recreated saloon, gold mine tours, narrow-gauge train, gunfight shows, Superstition Mountain Museum |

| Nearby Landmark | Base of the Superstition Mountains and near Apache Junction, AZ |

| Access | Easily accessible via AZ Highway 88 (Apache Trail) |

| Elevation | Approx. 2,000 feet (610 meters) |

| Climate | Sonoran Desert – hot summers, mild winters |

| Best For | Families, photographers, Old West lovers, Superstition Mountain hikers |

| Notable Lore | Near the alleged site of the Lost Dutchman’s Gold Mine |

Goldfield’s story begins with the discovery of gold in the Superstition Mountains region in 1892. Prospectors had long searched the area, partly inspired by legends of the Lost Dutchman’s Mine, when a significant gold-bearing quartz vein was discovered on the eastern slope of Superstition Mountain. Within months of the initial strike, word spread throughout the territory and beyond, drawing experienced miners from established fields in California, Colorado, and Nevada.

The town was officially established in 1893, strategically located near the Mammoth Mine, which would become the area’s richest producer. From the beginning, gold was the singular economic driver of Goldfield’s existence. Unlike some mining operations that required complex industrial processes, the gold here was found in high-grade ore that could be processed relatively easily, making it attractive to both individual miners and larger mining companies seeking quick returns on investment.

At its peak between 1893 and 1897, Goldfield boasted an impressive population of approximately 4,000 people—a substantial figure for a frontier mining town in territorial Arizona. This rapid growth reflected the richness of the initial ore discoveries and the optimism that pervaded the community during its early years. The settlement quickly developed beyond a mere mining camp to include all the amenities of a proper town, including substantial commercial buildings, residences, and community institutions.

Goldfield’s development occurred during a significant period in Arizona’s territorial history. The 1890s represented a time of transition as the frontier period was giving way to more established governance and infrastructure. The territory was experiencing growth in agriculture, ranching, and mining, with communities like Phoenix, Tucson, and Prescott expanding their influence. Goldfield’s gold boom coincided with increased railroad development throughout the territory, though the town itself would struggle with transportation challenges that would ultimately contribute to its decline.

Notable events during Goldfield’s brief heyday included the visit of territorial governor Louis C. Hughes in 1894, who reportedly declared the settlement “a model mining community with promise to rival the great camps of the West.” The town also weathered the economic uncertainties of the Panic of 1893, largely insulated by the intrinsic value of its gold production during a time when many silver-based communities suffered from falling silver prices following the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.

Today’s Goldfield presents visitors with a curious blend of authentic historical remains and thoughtful reconstruction. Unlike many ghost towns that have disappeared entirely or exist only as scattered ruins, Goldfield has experienced a partial rebirth as a tourist destination that seeks to capture the spirit of its 1890s heyday.

The original townsite, located on private land, has been developed into Goldfield Ghost Town, a tourist attraction that combines preserved historical structures with reconstructed buildings designed to evoke the appearance of the mining boomtown. The main street features boardwalks fronting a collection of period-appropriate storefronts including a saloon, general store, and assay office. Some buildings incorporate materials salvaged from the original structures, while others have been constructed using historical photographs as references.

Among the most notable authentic remains is the entrance to the Mammoth Mine, now secured but visible as part of guided tours. Several original mining equipment pieces are displayed throughout the site, including an ore cart, stamp mill components, and various hand tools that offer glimpses into the labor-intensive process of hard-rock gold mining in the 1890s.

The infrastructure of the original town is partially represented through reconstructed elements. A water tower stands near the center of town, reminiscent of the original that supplied the community during its productive years. The street layout generally follows historical patterns, though adapted for modern visitor circulation and safety requirements.

Preservation efforts began in earnest in the 1960s when private owners recognized the historical and commercial value of the site. Subsequent development has focused on balancing historical accuracy with visitor amenities and safety. Archaeological work conducted in the 1980s and 1990s helped identify the precise locations of original structures and recovered numerous artifacts now displayed in the town’s small museum.

Accessibility for modern visitors is excellent, with Goldfield Ghost Town located just off State Route 88 (the Apache Trail), approximately 45 minutes from downtown Phoenix. The site offers guided tours, demonstrations of period mining techniques, and various entertainment options designed to give visitors a sense of life in a mining boomtown. While the commercial nature of the site necessarily affects its historical authenticity, it has preserved and interpreted a history that might otherwise have been lost to the desert elements.

Set against the rugged backdrop of the Superstition Mountains, approximately a quarter mile north of the main settlement, Goldfield’s pioneer cemetery offers perhaps the most authentic connection to the town’s original inhabitants. Established almost immediately after the town’s founding in 1893, this burial ground served as the final resting place for Goldfield’s earliest residents during the initial boom years.

The cemetery occupies approximately half an acre on a gentle slope overlooking what was once the bustling center of mining activity. Today, it contains approximately 30 visible grave markers, though historical accounts and archaeological surveys suggest that between 50 and 80 individuals may have been buried here during the town’s brief existence. The cemetery remained active from 1893 until approximately 1898, coinciding with the productive years of the mines and the town’s subsequent decline.

The surviving markers reflect both the hastily established nature of the community and the diverse backgrounds of those who ventured to this remote outpost. Most are simple stone cairns or wooden crosses, many weathered beyond legibility by the harsh desert climate. Several more substantial markers remain, including a few carved sandstone headstones and cast iron crosses that have better withstood the passage of time. These more permanent monuments typically belonged to wealthier mine owners or successful merchants who could afford such luxuries on the frontier.

The cemetery reveals patterns common to mining boomtowns of the era. The predominantly male population is reflected in the burial records, with men outnumbering women approximately four to one. Several markers indicate deaths from mining accidents, including a row of three graves commemorating miners killed in a single cave-in at the Black Queen Mine in November 1895. Other causes of death evidenced in the burial records include typhoid (which swept through the community in the summer of 1894), pneumonia, and the occasional violence that erupted in saloons and gambling establishments.

One of the more poignant aspects of the cemetery is a small section containing the graves of approximately a dozen children, most under the age of five—stark testimony to the harsh realities of frontier life and the limited medical care available in remote mining communities. Several of these graves feature small toys or shells as grave decorations, reflecting the common Victorian mourning practices of the period.

The cemetery exists today in a state of respectful preservation. Unlike the more commercialized areas of Goldfield Ghost Town, the pioneer cemetery remains a solemn space where visitors are encouraged to reflect on the human cost of frontier development. Basic maintenance is performed regularly, with volunteer groups occasionally clearing overgrowth and making minor repairs to damaged markers. However, the site maintains its weathered, authentic character, allowing visitors to experience a genuine connection to Goldfield’s past.

Beyond the confines of the pioneer cemetery, a broader pattern of burials developed as Goldfield matured. Approximately one mile east of town, a larger community cemetery was established around 1895, reflecting both the settlement’s growth and increasing social stratification. This second burial ground served the community until well after the initial mining boom had subsided, with occasional burials continuing into the early 1900s even as the town itself declined.

The community cemetery, covering approximately two acres, contains an estimated 100-120 graves arranged in a more formal pattern than the pioneer cemetery. Here, family plots became more common, with low stone walls or iron railings sometimes delineating these areas. The organization reflects the evolution of Goldfield from a chaotic boomtown to a more structured community with defined social hierarchies and established families.

The demographic representation in this secondary burial ground differs notably from the pioneer cemetery. Records and remaining markers suggest a more diverse population, including a higher proportion of women and children, indicating that as the town stabilized, more miners brought families to the area. Several sections of the cemetery reflect the ethnic diversity of later Goldfield, including areas where Mexican miners and their families were buried, often with distinctive Catholic crosses and Spanish inscriptions.

The gravestones themselves tell a story of a maturing community. Many show evidence of professional craftsmanship imported from Phoenix or even further afield, replacing the improvised markers of the earlier cemetery. Religious symbolism is more prevalent, with Christian denominations well-represented through crosses, biblical verses, and symbolic imagery like lambs (for children) and clasped hands (for married couples).

Community traditions around burial evolved as Goldfield developed. While early interments were often hasty and pragmatic affairs, later burials involved more formal ceremonies. A diary account from 1896 describes a funeral procession “led by Reverend Williams and the members of the Masonic Lodge in full regalia, with nearly half the town in attendance” for the burial of Alexander Stevens, a prominent mine superintendent. Such accounts suggest that funeral practices became important community rituals that reinforced social bonds in the isolated mining town.

Notable individuals buried in the community cemetery include James Beard, one of the original discoverers of gold in the area, who died in 1896 after selling his claim for a substantial sum; Margaret Wilson, who operated the town’s first school until her death from tuberculosis in 1897; and Dr. Thomas Reynolds, whose medical practice served the community throughout its productive years until his own death in 1898—reportedly from exhaustion after treating victims of a influenza outbreak.

Today, the community cemetery exists in a state of preservation similar to the pioneer cemetery, though it receives somewhat less attention from visitors to the Goldfield Ghost Town attraction. Archaeological surveys conducted in the early 2000s documented the remaining markers and grave locations, contributing valuable information to genealogical records and historical understanding of the community’s demographics.

Goldfield’s rapid development as a significant mining center merited its own newspaper, the Goldfield Nugget, which began publication in August 1893, just months after the town’s founding. Established by editor and publisher William Beard (no relation to miner James Beard), the weekly paper operated from a wooden structure on Miners Avenue, using a second-hand Washington hand press transported from Phoenix at considerable expense.

The Nugget quickly established itself as both the town’s voice and its connection to the broader territory. With a peak circulation of approximately 500 copies, the paper reached not only local residents but also investors in Phoenix, Tucson, and even as far as San Francisco and Denver. This wider distribution played a crucial role in attracting additional capital and settlers to the burgeoning mining district.

Politically, the Nugget reflected the predominantly Republican leanings of many mining communities in the 1890s, frequently advocating for sound money policies and protective tariffs that benefited mining interests. Editor Beard was not shy about using his editorial column to campaign for improvements to the town, including better roads to Phoenix, telegraph service, and eventually, hopes for a railroad spur that never materialized.

The newspaper documented the community’s rapid development, reporting on new mine openings, ore discoveries, business establishments, and social events that formed the rhythm of life in Goldfield. Its pages recorded the construction of substantial buildings like the two-story Mammoth Hotel in 1894, the opening of the Goldfield School in 1895, and the formation of community organizations including the Miners’ Protective Association and the Ladies’ Aid Society.

The Nugget did not shy away from reporting on the community’s challenges. Coverage included accounts of the typhoid outbreak in 1894, a devastating fire that destroyed several wooden structures along Commercial Street in early 1896, and occasional violence that erupted in the town’s saloons and gambling establishments. These accounts, while sometimes sensationalized, provide historians with valuable insights into daily life in Goldfield.

A second, shorter-lived publication, the Superstition Sentinel, began operation in May 1895, representing competing business interests within the growing community. Published by Thomas Reynolds (the same doctor buried in the community cemetery), this rival paper took a more Democratic editorial stance and frequently criticized what it considered the boosterism of the Nugget. The competition between the two papers—sometimes friendly, sometimes acrimonious—offers researchers multiple perspectives on community events and controversies.

Both newspapers operated from physical offices that served as important community gathering places. The Nugget office, in particular, functioned as an informal information exchange where miners would bring news of new strikes or accidents, travelers would share information from other settlements, and community notices would be posted. The printing presses themselves were objects of considerable pride, representing technological advancement and connection to the wider world of ideas and commerce.

As Goldfield’s fortunes declined in the late 1890s, so too did its newspapers. The Sentinel ceased publication in October 1896 when Reynolds sold his press and returned to medical practice full-time. The Nugget continued until April 1898, with increasingly desperate editorials urging new investment and diversification beyond gold mining. The final edition announced the paper’s relocation to the more promising community of Globe, where editor Beard hoped to find a more sustainable business environment.

Surviving copies of these newspapers are rare but valuable resources for understanding Goldfield’s brief but vibrant existence. The Arizona Historical Society maintains a partial collection of the Nugget, with approximately 60 issues preserved on microfilm. Only a handful of Sentinel issues survive, primarily in private collections and occasional fragments in the Arizona State Archives.

Transportation infrastructure played a crucial role in Goldfield’s development and eventual decline. Unlike some more fortunate mining centers, Goldfield never secured the direct railroad connection that might have extended its productive life, instead relying on a network of wagon roads and stage lines that connected it to Phoenix and the outside world.

The nearest railroad during Goldfield’s heyday was the Maricopa & Phoenix Railroad, which terminated in Phoenix approximately 35 miles southwest of the mining district. This distance, though not insurmountable, created significant challenges for shipping ore, bringing in heavy equipment, and moving people efficiently. The transportation gap was filled by stage and freight lines that made the journey between Phoenix and Goldfield three times weekly during the peak years.

The primary stage company serving Goldfield was the Arizona Stage & Freight Company, which established operations in early 1894. The company constructed a substantial depot and stables on the western edge of town, employing several drivers and hostlers to maintain coaches and teams. The stage service provided both passenger transportation and mail delivery, with the Goldfield post office established in December 1893 operating from a corner of the general store until a dedicated building was constructed in 1895.

The physical infrastructure of transportation, while less visible today than mining ruins, played an important role in the community. The main road connecting Goldfield to Phoenix—roughly following the path of today’s Apache Trail—was improved in 1894 through community subscription, with mine owners and merchants contributing funds to blast troublesome rock formations and construct rudimentary bridges over washes. This improved road reduced travel time from nearly eight hours to about five, a significant improvement for freight haulers and passengers alike.

Freight service was critical to Goldfield’s operations. Specialized freight wagons hauled ore from the mines to Phoenix for further transport to smelters in El Paso or California, while bringing back mining equipment, construction materials, and commercial goods for the growing community. The Mammoth Freight Company, established in 1895, operated large wagons pulled by teams of up to 12 mules, capable of hauling several tons of material per trip. The freight yard located at the edge of town became a hub of activity, with teamsters, merchants, and miners converging to conduct business.

The impact of these transportation systems on town life was substantial. Stagecoach arrivals became community events, with residents gathering to receive mail, welcome newcomers, or hear news from Phoenix and beyond. The schedule of freight deliveries dictated the rhythm of commercial activity, with stores restocking and mines receiving equipment according to the predictable pattern of wagon arrivals.

Transportation costs significantly affected Goldfield’s economic viability. Shipping ore to distant smelters reduced profit margins, particularly as the quality of ore began to decline after 1896. Similarly, bringing heavy mining equipment to the district was expensive, limiting the ability of mine operators to implement newer technologies that might have allowed exploitation of lower-grade ores as the richest veins were depleted.

The town’s failure to secure a railroad connection, despite several promising proposals between 1894 and 1896, ultimately contributed to its decline. When the Phoenix & Eastern Railroad (later part of the Southern Pacific system) was constructed through the Salt River Valley in 1903, it bypassed the already-fading Goldfield district, choosing instead a route through Mesa and toward the more productive mining districts around Globe and Miami.

Today, little physical evidence remains of Goldfield’s transportation infrastructure beyond traces of the original wagon roads visible in aerial surveys. The reconstructed Goldfield Ghost Town includes a representation of the stage depot, though not on its original location, providing visitors with a sense of this crucial aspect of frontier mining communities.

Goldfield’s decline began gradually around 1897, when the rich surface deposits that had fueled the initial boom began showing signs of depletion. The decline accelerated through 1898 as a combination of geological, economic, and technological factors conspired against the settlement’s continued viability.

The gold veins themselves presented the first and most fundamental challenge. As surface deposits were exhausted, mining operations needed to follow the ore deeper underground, requiring more substantial capital investment in equipment and infrastructure. Several mines encountered water at depth, necessitating expensive pumping operations that reduced profit margins. Most critically, the high-grade ore that had made the district so attractive initially began giving way to lower-quality deposits that were more expensive to process.

This geological reality coincided with financial pressures affecting mining investment nationally. While Goldfield had weathered the Panic of 1893 relatively well due to the intrinsic value of gold, by the late 1890s, capital for speculative mining ventures was becoming more cautious and concentrated in proven districts. New discoveries in the Klondike beginning in 1896 diverted investment and experienced miners northward, making it harder for Goldfield’s operations to secure necessary funding for expansion.

Technological limitations further complicated the district’s prospects. The lack of railroad access made importing advanced mining and milling equipment prohibitively expensive, preventing the kind of industrial-scale operations that might have profitably extracted lower-grade ores. The district’s water limitations also restricted milling operations, forcing some operators to transport ore to facilities along the Salt River at additional expense.

The timeline of decline was relatively clear in newspaper accounts and public records. By late 1897, the Nugget acknowledged that several smaller mines had ceased operations, though it maintained an optimistic tone about the prospects of the largest producers. In early 1898, the Mammoth Mine, the district’s anchor operation, reduced its workforce by half. By mid-1898, the town’s population had fallen below 1,000, with merchants and service providers following the miners in departing for more promising locations.

Census records from 1900 indicate that fewer than 150 residents remained in Goldfield, primarily caretakers maintaining mine properties, a few optimistic prospectors, and older residents unable or unwilling to start fresh elsewhere. The post office was officially discontinued in October 1898, requiring remaining residents to travel to Mesa for mail service—a sure sign of the community’s diminished status.

Most residents relocated to Phoenix, Mesa, or other mining districts in Arizona and beyond. Some followed the pattern common to career miners, moving from one boom town to another as opportunities shifted. Others abandoned mining altogether, turning to agriculture, commerce, or other professions in the region’s growing towns and cities.

The community infrastructure crumbled quickly as population declined. The school closed in spring 1898 when enrollment fell below 15 students. Churches, which had never built permanent structures, discontinued regular services around the same time. Commercial establishments either relocated or closed throughout 1898, with the last saloon reportedly shuttering in early 1899.

Both cemeteries saw decreasing activity as the town emptied, though occasional burials continued in the community cemetery until around 1910, primarily for longtime residents who had maintained connections to the area or for those who died while working small claims that continued to operate sporadically.

By 1900, Goldfield had effectively ceased to exist as a functioning community, though isolated prospectors and small-scale mining operations continued in the area well into the 20th century. A brief revival occurred between 1909 and 1911 when the Goldfield Consolidated Mining Company attempted to reopen several mines using more modern techniques, but this effort proved short-lived and involved only a small workforce housed in temporary camps rather than rebuilding the town.

Goldfield occupies an important place in Arizona’s territorial development and mining history. While shorter-lived than more famous mining centers like Jerome or Bisbee, it exemplifies the rapid boom-and-bust cycle that characterized many Western mining ventures in the late 19th century. The town’s rise and fall paralleled hundreds of similar communities across the American West, where the discovery of precious metals could create instant prosperity that disappeared just as quickly when deposits were exhausted.

Archaeological investigations conducted at the Goldfield site beginning in the 1960s have documented the physical remains of the mining operations and town infrastructure. These studies identified building foundations, mining features, artifact concentrations, and consumption patterns that provide valuable insights into daily life in a 1890s mining community. The findings have contributed to scholarly understanding of mining technology, frontier commerce, and community development in territorial Arizona.

The site gained official historical recognition in 1980 when the Goldfield Mining District was added to the Arizona Register of Historic Places, acknowledging its significance in the territory’s economic and social development. This designation provides certain protections for the archaeological resources while recognizing the area’s educational and cultural value.

For the local indigenous communities, particularly the Akimel O’odham (Pima) and Tohono O’odham, whose traditional territories encompassed the region, the Goldfield area holds cultural significance that both predates and outlasts the brief mining boom. Several traditional plant gathering areas and seasonal pathways exist in the vicinity, and tribal historians maintain knowledge of interactions between O’odham people and the miners of Goldfield, including labor relationships and occasional conflicts over resource access.

Today, Goldfield Ghost Town serves as an important heritage tourism destination, attracting over 200,000 visitors annually. While the commercialized nature of the site necessarily affects its historical authenticity, it has preserved and interpreted a chapter of Arizona history that might otherwise have been lost to development or erosion. The site offers educational programming for school groups, interpretive exhibits on mining technology and frontier life, and seasonal events that commemorate aspects of the area’s history.

Beyond tourism, Goldfield has secured a place in regional folklore through its proximity to the Superstition Mountains and the legendary Lost Dutchman’s Mine. Though the actual mining operations at Goldfield were unrelated to this famous legend, the historic mining district has become intertwined with the broader mythologies of hidden treasure and frontier adventure that continue to draw prospectors and curiosity-seekers to the region.

The preservation status of Goldfield’s cemeteries reflects a balance between historical authenticity and practical conservation. The pioneer cemetery, with its earlier and more primitive markers, has received attention from both professional conservators and volunteer groups since the 1970s. Basic preservation measures have included clearing vegetation, stabilizing deteriorating markers, and documenting inscriptions before they are lost to weathering.

The Arizona Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project has been particularly active at the site, conducting systematic surveys in 2003 and again in 2014 to document remaining graves and create a comprehensive database of burials. Their work has combined traditional documentation methods with newer technologies including ground-penetrating radar to identify unmarked graves and digital mapping to create precise cemetery plans that aid both conservation efforts and genealogical research.

The community cemetery, being slightly larger and containing more substantial monuments, has benefited from similar preservation efforts, though its more remote location has resulted in less regular maintenance. The East Valley Historical Society, in cooperation with the current property owners, organizes annual cleanup events that clear brush, repair damaged fencing, and document changes to the site caused by erosion or vandalism.

Memorial practices at both cemeteries have evolved over time. During Goldfield’s active years, decoration of graves followed patterns common to the Victorian era, with regular maintenance of family plots and community observances on Decoration Day (later Memorial Day). As the town declined, these formal practices gave way to more sporadic visitation by relatives or former residents.

Today, a combination of official and informal commemorative activities keeps the memory of Goldfield’s pioneers alive. The Goldfield Ghost Town attraction includes the pioneer cemetery in its guided tours, providing historical context and biographical information about notable burials. This commercial interpretation is balanced by more personal remembrances, as descendants of Goldfield residents occasionally place flowers or small tokens at family graves, particularly around traditional memorial holidays.

More formal commemoration occurs through the Arizona Historical Society’s “Marking Forgotten Graves” program, which has installed several interpretive plaques at both cemetery sites explaining their significance and providing context about burial practices in mining communities. These markers serve both educational purposes for visitors and memorial functions for the community whose physical traces have largely disappeared.

The cemeteries have also become important resources for genealogical research, with several family history organizations maintaining records of burials and assisting descendants in locating ancestral connections to Goldfield. This ongoing research has sometimes led to the addition of new markers at previously unmarked graves when descendants discover family connections and choose to commemorate ancestors buried in these historic grounds.

For those wishing to experience Goldfield’s history firsthand, ethical considerations should guide any visit to this historic site. While the commercial Goldfield Ghost Town attraction provides a controlled and interpreted experience of the town’s history, the cemetery areas and outlying archaeological sites require particular respect and care from visitors.

The pioneer cemetery, included within the ghost town attraction, has established pathways and interpretive signage to guide visitors. When viewing this burial ground, visitors should remain on designated paths, refrain from touching or climbing on grave markers, and maintain appropriate decorum in what remains consecrated ground despite its tourism context. Photography is permitted but should be conducted respectfully, avoiding staged or inappropriate poses near graves.

The community cemetery, located outside the main attraction area, presents additional preservation challenges. Visitors should recognize that this site has less regular maintenance and security oversight, making respectful behavior particularly important. Those seeking specific graves should take care not to disturb surrounding vegetation or other markers, as the desert environment is fragile and slow to recover from damage.

Archaeological resources throughout the area face ongoing threats from both natural processes and human activity. Erosion, flash flooding, and plant growth continuously affect remaining structures and features. Meanwhile, unauthorized artifact collection—strictly prohibited by state and federal law—remains a serious concern at less monitored portions of the historic district. Visitors should understand that removing even seemingly insignificant objects depletes the site’s historical integrity and scientific value.

Official management of the various Goldfield sites is divided among several entities. The commercial ghost town attraction operates on private land with its own regulations and interpretive approach. The surrounding historic mining district includes lands managed by the Tonto National Forest, the Bureau of Land Management, and various private owners, each with different access policies and preservation standards. Visitors should research and respect these jurisdictional boundaries and applicable regulations.

For those seeking more information before or after a visit, several regional resources provide context and guidance. The Superstition Mountain Museum, located near the ghost town, offers exhibits on mining technology and local history. The Arizona Historical Society’s Central Arizona Museum in Tempe maintains archives related to Goldfield, including newspaper records and photographs. These institutions can provide depth and nuance beyond what is available at the commercial attraction.

The desert winds that once carried the sounds of stamp mills and miners’ calls now whisper through reconstructed boardwalks and around weathered headstones, telling a story of ambition, struggle, and impermanence. Goldfield stands as both a physical place and a metaphor for the boom-and-bust cycle that shaped so much of Arizona’s territorial development—a community conjured from wilderness by the promise of mineral wealth, only to fade back into the landscape when those resources were exhausted.

The twin cemeteries, with their silent testimony to hopes, hardships, and human connections, provide perhaps the most authentic remaining link to the people who briefly called this mining camp home. In their weathered inscriptions and carefully chosen locations, we glimpse the values and priorities of a generation that pushed the boundaries of settlement into Arizona’s challenging terrain, seeking fortune but often finding community, hardship, or early graves instead.

As a chapter in Arizona’s mining heritage, Goldfield’s brief existence paralleled hundreds of similar communities across the American West, where natural resources drew population rapidly, created momentary prosperity, and then faded just as quickly when those resources proved finite or inaccessible. This pattern of swift growth and decline shaped much of the territory’s early development and continues to influence modern Arizona’s relationship with its natural resources and historical legacy.

Today, as visitors walk the reconstructed streets or stand before pioneer grave markers, Goldfield offers a chance to reflect on the temporary nature of even our most substantial achievements. The town that once hummed with commerce and ambition lasted barely five years at its height—a reminder that all human ventures eventually yield to time and changing circumstances.

Yet in the historical record, and in the DNA of Arizona’s development, the legacy of these pioneer communities lives on—a testament to the resilience, adaptability, and unflagging optimism that characterized frontier settlement. The miners of Goldfield may have exhausted the accessible gold in the Superstition foothills, but they left behind something perhaps more valuable: a chapter in the complex, compelling story of how Arizona came to be.

In its preserved ruins, reconstructed buildings, and silent cemeteries, Goldfield invites modern visitors to connect with a pivotal moment in Western history—when the frontier was closing, industrial capitalism was transforming resource extraction, and communities could still spring fully-formed from the desert based on the promise of mineral wealth. That this particular promise proved fleeting makes the story no less significant in understanding the forces that shaped the modern American West.

Goldfield Ghost Town is located at 4650 N. Mammoth Mine Road, Apache Junction, AZ, approximately six miles northeast of Apache Junction proper, just off State Route 88 (Apache Trail). The site is well-marked and accessible by standard vehicles. The pioneer cemetery is located within the ghost town attraction, while the community cemetery is on public land approximately one mile east, with access requiring guidance from local historical organizations.

This article was researched and written based on historical documents, cemetery records, and archaeological surveys of the Goldfield site. The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the Superstition Mountain Museum, the Arizona Historical Society, and descendants of Goldfield pioneers who shared family histories and photographs.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By using our site, you consent to cookies.

Manage your cookie preferences below:

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.