Nestled in the high country of eastern Arizona, Springerville stands as a testament to the enduring spirit of the American Southwest. This small but vibrant community sits at an elevation of 7,000 feet in the White Mountains, where the vast Colorado Plateau meets the rugged wilderness. With a population of approximately 2,000 residents, Springerville serves as the commercial and cultural hub for the surrounding rural areas of Apache County. The town’s demographic makeup reflects its multicultural heritage, with significant Hispanic, Anglo, and Native American populations contributing to its unique character.

What truly sets Springerville apart is its remarkable position at the crossroads of natural splendor and human history. Here, ancient volcanic fields meet pioneer settlements, Native American heritage blends with ranching traditions, and small-town values persist against the backdrop of an ever-changing American landscape. As the self-proclaimed “Gateway to the White Mountains,” Springerville offers visitors and residents alike a genuine slice of Arizona’s diverse identity—where the Old West isn’t simply remembered but continues to live and evolve.

Today, Springerville’s history is preserved through institutions like the Springerville Heritage Center, which houses the Renee Cushman Art Museum, the Becker Family History Museum, and the Casa Malpais Archaeological Museum. Annual events like Pioneer Days celebrate the community’s frontier roots, while collaboration with the White Mountain Apache Tribe acknowledges the area’s indigenous heritage. Street names, architectural elements, and family names throughout town provide daily reminders of the layers of history that have shaped this resilient mountain community.

The story of human presence in what is now Springerville begins thousands of years ago with indigenous peoples who recognized the value of this well-watered valley. The area was home to the ancient Mogollon culture, whose presence is still evident in nearby archaeological sites, particularly at Casa Malpais—a national historic landmark featuring a prehistoric pueblo complex. The Apache people later claimed these mountains as their territory, with the White Mountain Apache developing a profound relationship with the land that continues to this day.

European settlement came relatively late to this remote corner of Arizona. In 1871, William Milligan established a trading post along the Little Colorado River, but it was Henry Springer, a German immigrant and entrepreneur, who in 1879 purchased the settlement and gave it his name. The arrival of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad (later the Santa Fe) in nearby Holbrook accelerated growth in the region, as Springerville became an important supply center for ranchers, loggers, and miners.

The town’s history reflects the broader struggles of the American frontier—conflicts between indigenous peoples and settlers, range wars between cattle ranchers and sheep herders, and the harsh realities of carving out a life in a demanding environment. Notable figures from Springerville’s past include Ike Clanton of OK Corral infamy, who met his end near here, and the infamous Apache warrior Geronimo, who roamed these mountains.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Location | Northeastern Arizona, Apache County, adjacent to Eagar |

| Founded | 1879 (named after settler Henry Springer) |

| Incorporated | 1948 |

| Population | Approx. 1,800 (as of the 2020 Census) |

| Elevation | ~6,974 feet (2,126 meters) — one of Arizona’s highest towns |

| Climate | Cool four-season mountain climate; mild summers, snowy winters |

| Known For | Outdoor recreation, volcanic geology, historic preservation |

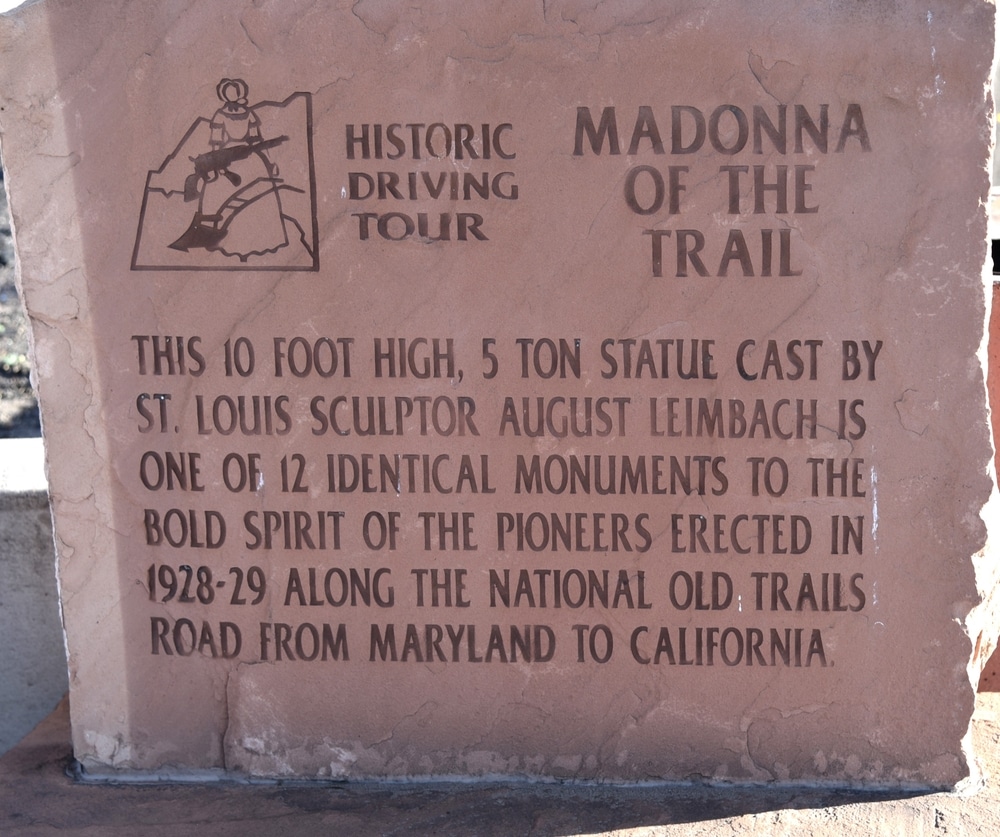

| Major Attractions | Casa Malpaís Archaeological Park, Becker Lake, White Mountain Grasslands, Madonna of the Trail statue |

| Key Industries | Tourism, government (Apache County offices), ranching, small business |

| Cultural Significance | Native American heritage (Zuni & Apache), Mormon pioneer settlement, historic ranching community |

| Annual Events | Springerville Heritage Festival, Christmas Light Parade, ATV and rodeo events |

| Transportation | Located on U.S. Routes 60, 180, and 191; accessible via scenic mountain byways |

| Education | Round Valley Unified School District (shared with Eagar) |

| Nearby Natural Sites | Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest, Mount Baldy, Sunrise Park Resort, Luna Lake |

| Outdoor Activities | Hiking, fishing, hunting, ATV riding, skiing, camping |

| Community Features | Museums, visitor center, historic churches, regional health services |

| Regional Note | Part of the “Round Valley” twin towns area along with Eagar |

Springerville stands as a microcosm of the cultural blending that characterizes much of the American Southwest. The influence of Native American traditions runs deep, particularly those of the White Mountain Apache, whose reservation borders the community. These indigenous roots are evident in art, craftsmanship, and place names throughout the region. Hispanic culture—bringing Spanish language, Catholic traditions, and distinctive architectural styles—has been central to the area’s identity since early settlement days, while Anglo-American pioneers contributed ranching traditions, Protestant religious practices, and governmental structures.

Unlike some communities where cultural traditions remain distinctly separated, Springerville has experienced significant blending over generations. This is perhaps most evident in local cuisine, where Native American ingredients, Hispanic cooking techniques, and Anglo adaptations have created distinctive regional dishes. Similarly, religious celebrations often incorporate elements from multiple traditions, creating uniquely Springerville expressions of faith and community.

Language in Springerville reflects this cultural intermingling. While English predominates, Spanish remains vibrant within many families and businesses. Local speech patterns often incorporate distinctive Western ranching terminology, Spanish phrases, and occasionally Apache words, particularly for local plants, animals, and geographic features. Longtime residents speak with a distinctive accent that combines Western and Southwestern influences—what locals sometimes call “Mountain Talk.”

Cultural preservation efforts are spearheaded by several organizations, including the Springerville-Eagar Chamber of Commerce, the Round Valley Public Library, and various church communities. Elders from all cultural backgrounds are respected as keepers of local knowledge, with programs in place to record their stories and skills. The White Mountain Historical Society works to document both indigenous and settler histories, recognizing that the complete story of Springerville requires multiple perspectives.

Recent decades have brought shifts to Springerville’s cultural landscape. Tourism has introduced new economic opportunities while creating pressure for the community to commodify its heritage. The internet has connected even this remote town to global cultural influences, particularly evident among younger residents. Yet through these changes, Springerville maintains a distinctive identity—one that continues to evolve while honoring its multicultural foundations.

Springerville’s artistic expression is deeply rooted in its natural surroundings and diverse cultural influences. The dramatic landscapes of the White Mountains, volcanic fields, and expansive skies have inspired generations of artists drawn to the area’s remarkable light and geological features. This inspiration is evident in the prevalence of landscape painting, photography, and pottery that references local landforms and native materials.

Traditional arts remain vibrant, with Native American influences seen in weaving, beadwork, and basketry created by both indigenous and non-indigenous artisans. Hispanic artistic traditions are visible in woodcarving, santos (religious icons), and metalwork. Western artistic themes—particularly those celebrating ranching life—appear in leather crafting, horsehair weaving, and representational sculpture found throughout the community.

Notable artists with connections to Springerville include early 20th-century photographer Burton Frasher, whose images documented the area’s development; contemporary painter William Gardner, known for capturing the unique quality of mountain light; and sculptor Deborah Copenhaver Fellows, whose bronze works celebrate the ranching heritage. The Renee Cushman Art Collection at the Springerville Heritage Center houses an unexpected treasure—European art and artifacts collected by a local who inherited a fortune and traveled extensively in the early 20th century.

Artistic spaces in Springerville range from formal to improvised. The Springerville Heritage Center serves as the primary gallery space, while local businesses frequently display work by area artists. The Round Valley Public Library hosts rotating exhibitions, and seasonal art fairs bring together creators from across the region. Several working artists maintain studios in and around town, some offering workshops and demonstrations to visitors.

Art education happens both formally and informally in Springerville. The Round Valley Unified School District maintains active visual and performing arts programs, often incorporating local cultural elements and artistic traditions. The community’s senior center offers classes in traditional crafts, while private instructors teach everything from traditional Apache beadwork to contemporary painting techniques. This commitment to artistic education ensures that Springerville’s creative traditions continue to evolve while maintaining their distinctive regional character.

The last weekend in July transforms Springerville into a living museum of frontier life. Established in 1956 to commemorate the town’s founding, Pioneer Days features historical reenactments, traditional craft demonstrations, and a parade showcasing vintage vehicles and period costumes. Local families proudly display artifacts passed down through generations, while the Dutch oven cook-off highlights foods that sustained early settlers. The festival has grown from a small local commemoration to a regional attraction drawing visitors from across Arizona and New Mexico.

Each June, the skies above Springerville fill with the colorful canopies of hot air balloons, creating a spectacular contrast against the volcanic landscape. This three-day celebration centers around dawn and dusk balloon launches but has expanded to include a street fair, live music, and children’s activities. The event brings together pilots from across the Southwest, fostering friendly competition while creating economic opportunity during the crucial summer tourism season. Evening balloon glows—where tethered balloons illuminate like giant lanterns—have become the festival’s most photographed and beloved tradition.

Held during the first weekend of August, this celebration of indigenous creativity showcases traditional and contemporary works by Native American artists, particularly those from the neighboring White Mountain Apache Tribe. Established in 1989, the market features juried competition in categories including weaving, jewelry, pottery, and painting. Demonstrations of traditional techniques pass knowledge to younger generations, while performances of Apache crown dancers and other cultural presentations educate visitors. The market has become an important economic opportunity for indigenous artists while strengthening cultural connections within the broader community.

This November gathering embodies the town’s commitment to ensuring no one faces the holiday alone. Organized by an interfaith coalition of local churches, the community-wide dinner serves hundreds, bringing together residents of all backgrounds for a meal that combines traditional Thanksgiving dishes with regional specialties. Dozens of volunteers cook, serve, and deliver meals to homebound residents. What began in 1978 as a small church basement gathering has grown into a town-wide tradition that particularly welcomes newcomers, seasonal workers, and those facing hardship—a living expression of Springerville’s communal values.

December brings this relatively new but already beloved celebration combining holiday shopping, winter activities, and community fundraising. Launched in 2008, the festival includes a nighttime light parade, craft markets featuring local artisans, and a chili cook-off that generates good-natured competition between local restaurants and organizations. Its centerpiece is the “Trees of Giving” auction, where decorated Christmas trees are sold to benefit local charities. The festival has evolved to embrace Springerville’s winter identity rather than trying to replicate warm-weather celebrations, creating a distinctive event that celebrates the beauty and challenges of mountain winters.

Ask residents to describe Springerville, and certain phrases consistently emerge: “small town with a big heart,” “where everybody knows your name,” and the semi-official “Gateway to the White Mountains.” These characterizations reflect the community’s self-image as a place where personal connections matter and natural beauty remains central to daily life. The town sometimes calls itself “Arizona’s Volcano Town,” acknowledging the dramatic landscapes created by the Springerville Volcanic Field with its more than 400 cinder cones.

Architecturally, Springerville displays a practical vernacular style that reflects its ranching heritage and mountain environment. Downtown features early 20th-century commercial buildings of native stone and brick, while residential areas showcase a mix of Western ranch-style homes, traditional adobe structures, and simple mountain cabins. New construction increasingly incorporates elements of mountain rustic style, with prominent use of timber, stone, and metal roofing designed to withstand heavy winter snows.

The community values of self-reliance and neighborliness manifest throughout Springerville. Residents take pride in their ability to handle harsh weather, geographic isolation, and limited resources—yet they’re quick to help neighbors facing difficulties. This combination of independence and interdependence shapes the community’s character, creating a place where people value both personal freedom and collective responsibility.

When describing their community to outsiders, residents often emphasize Springerville’s authenticity. Unlike some Western towns that have become tourist caricatures, Springerville remains a working community where ranching, small business, and public service form the economic backbone. Locals take pride in the town’s unpretentious nature, often noting that “what you see is what you get” in Springerville—a place where practical concerns trumps appearances and where a person’s word still carries significant weight.

This authenticity extends to the community’s approach to its history and heritage. Rather than offering a sanitized version of the past, Springerville acknowledges both the achievements and struggles that have shaped it, creating a nuanced sense of place that honors complexity rather than myth-making. This honest approach to community identity has helped Springerville maintain its distinctive character even as economic and social changes reshape the American Southwest.

Springerville operates under a council-manager form of government, with a mayor and four council members elected to four-year terms. The Town Manager handles day-to-day operations with a small staff providing essential services. This governmental structure reflects Springerville’s practical approach to community management—focused on basic services while allowing for significant citizen input. The town collaborates closely with neighboring Eagar on many services, creating efficiencies that benefit both communities.

Beyond formal government, civic participation flourishes through numerous organizations that address community needs. The Springerville-Eagar Chamber of Commerce advocates for business interests while organizing community events. Service organizations like the Rotary Club and Lions Club maintain active local chapters focused on youth programs and community improvement. Faith communities—including several Protestant denominations, a Catholic parish, and Mormon wards—provide both spiritual guidance and practical assistance, particularly for vulnerable residents.

The Round Valley Community Council serves as an informal but influential forum where residents discuss pressing issues before they reach the town council. Monthly meetings in the high school cafeteria regularly draw dozens of participants, providing a venue for airing concerns and building consensus. This grassroots approach to problem-solving has addressed challenges from water conservation to youth recreation, often finding solutions before formal intervention becomes necessary.

Notable community-led initiatives include the Springerville Community Garden, which provides fresh produce for the local food bank while teaching gardening skills; the Friends of the Round Valley Public Library, whose fundraising has significantly expanded library collections and programming; and the Round Valley Trail Association, which has developed and maintains an extensive network of recreational trails connecting the town to surrounding natural areas. These volunteer-driven efforts demonstrate how Springerville residents take ownership of community needs rather than waiting for governmental solutions.

Springerville’s economy has historically rested on what locals call “the three Rs”—ranching, retail, and recreation. Cattle ranching remains significant, with several multi-generational operations maintaining traditions that date back to the town’s founding. Retail businesses serve both locals and travelers along Highway 60, with Springerville functioning as a commercial hub for a large but sparsely populated region. Recreational tourism has grown increasingly important, with visitors drawn to the area’s hunting, fishing, hiking, and winter sports opportunities.

The public sector provides stable employment through the school district, the U.S. Forest Service, and municipal government. The Coronado Generating Station, a coal-fired power plant located nearby, has been a major employer since the 1970s, though its future remains uncertain as Arizona transitions toward renewable energy. Healthcare has emerged as a growth sector, with the Round Valley Community Medical Center expanding services to meet the needs of an aging population.

Small businesses form the backbone of Springerville’s economy, with entrepreneurship deeply ingrained in the community’s identity. Western Drug, established in 1926, remains locally owned and operated, as do numerous restaurants, outfitters, and specialty retailers. Newer entrepreneurial ventures include a craft brewery, several bed-and-breakfast operations, and remote workers who have relocated, bringing digital careers to this traditional community.

Local products distinctive to Springerville include handcrafted leather goods from several workshops, wool products from area ranches, and specialty foods like high-altitude honey and pine nut confections. The Round Valley Farmers Market provides a venue for local producers during summer months, while the annual Christmas Bazaar showcases artisanal crafts that often incorporate local materials and regional motifs.

Economic challenges include the community’s geographic isolation, limited workforce housing, and vulnerability to economic downturns that affect tourism. Opportunities lie in the growing interest in authentic rural experiences, the expansion of outdoor recreation, and the possibility of attracting remote workers seeking small-town quality of life. Springerville’s economic development strategy balances growth with preservation, recognizing that the community’s distinctive character represents a valuable asset in itself.

The Round Valley Unified School District serves as the educational and often cultural heart of Springerville. With an elementary school, middle school, and high school located in town, education happens within a tight-knit community where teachers often instruct the children of their former students. The district takes pride in balancing academic achievement with practical skills, maintaining strong programs in agricultural education, building trades, and traditional arts alongside college preparatory curriculum.

Distinctive educational initiatives include the White Mountain Archaeological Field School, which involves students in excavations at nearby archaeological sites; the Heritage Studies program, where high school students document local history through oral interviews and archival research; and the Friends of the Forest program, which partners with the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest to provide environmental education in one of the nation’s largest ponderosa pine forests.

The Round Valley Public Library serves as an important educational resource beyond formal schooling. Its collection emphasizes regional history, practical skills, and literature about the American Southwest. The library’s digital resources have become increasingly important, providing residents with access to online learning and professional development opportunities that would otherwise require travel to distant urban centers.

Informal education flourishes through community workshops, where traditional skills are passed between generations. The annual Heritage Skills Weekend offers instruction in everything from Dutch oven cooking to rawhide braiding, saddle repair to quilting. The Senior Center’s knowledge exchange program pairs older residents with youth for the transmission of traditional knowledge, creating meaningful intergenerational connections while preserving practical wisdom.

The relationship between Springerville residents and their natural surroundings is fundamental to community identity. Located where the Colorado Plateau rises to meet the White Mountains, the town sits amid remarkable geological diversity—from ancient volcanic fields to pine forests, alpine meadows to rugged canyons. This varied landscape has shaped local culture, economy, and recreation for generations.

Traditional knowledge of local plants and their uses remains strong in Springerville. Many residents maintain familiarity with edible and medicinal species, including piñon pine nuts harvested in fall, wild berries collected throughout summer, and various medicinal plants gathered according to seasonal availability. This knowledge represents a blend of Native American, Hispanic, and Anglo traditions, adapting over generations to local conditions.

Conservation ethic runs deep in the community, with many families having witnessed landscape changes over decades. The White Mountain Conservation League, founded in 1984, advocates for responsible land management and sustainable use of natural resources. Its annual watershed restoration projects bring together diverse stakeholders—ranchers, anglers, hunters, and conservationists—who might disagree on politics but share commitment to land stewardship.

Outdoor traditions define Springerville’s recreational culture. Hunting remains both sport and subsistence activity for many families, with elk, deer, and turkey seasons marked on calendars alongside holidays. Fishing the mountain streams represents another multigenerational tradition, with favorite spots handed down like family heirlooms. The development of the Round Valley Trail System has created new recreational opportunities closer to town, while programs like the annual “First Fish” derby introduce newcomers to outdoor traditions that have sustained the community for generations.

Springerville’s cuisine reflects its position at the crossroads of Native American, Hispanic, and Anglo-American traditions, adapted to high-altitude conditions and seasonal availability. Traditional dishes include hearty stews that combine indigenous ingredients like corn, beans, and squash with European-introduced meats; sourdough biscuits that recall pioneer cooking methods; and distinctive preparations of local game, particularly elk and venison.

The community takes particular pride in its chile-based recipes, which showcase both red and green varieties prepared according to techniques that blend Hispanic traditions with local adaptations. Annual competitions for the best chile recipes—whether in stews, smothered burritos, or standalone sauces—generate friendly rivalry between families and restaurants. These dishes connect current residents to the agricultural and culinary practices of previous generations.

Local ingredients unique to the area include piñon nuts harvested from native pines, high-country honey produced by local apiaries, wild mushrooms gathered during monsoon season, and beef from cattle raised on native grasses. The short growing season has historically limited local agriculture, but the development of the Round Valley Community Garden and several small commercial greenhouse operations has extended availability of fresh produce.

Establishments that preserve culinary traditions include the Corral Restaurant, where ranch-style breakfasts follow recipes little changed since its opening in 1959; the Trail Rider, known for Dutch oven desserts that recall cowboy cooking methods; and Java Blues, which combines contemporary coffee culture with traditional local ingredients in creations like piñon lattes. These establishments serve not just as dining venues but as community gathering spaces where food traditions are shared and celebrated.

The physical spaces where Springerville residents come together reveal much about community values and social structure. The town’s traditional center, Main Street (Highway 60), remains an important commercial and social hub despite competition from newer developments. Here, institutions like Western Drug with its vintage soda fountain continue to function as informal meeting places where conversations bridge generations and social groups.

The Round Valley Dome—a distinctive multi-purpose facility housing sporting events, graduation ceremonies, and community celebrations—represents the community’s investment in shared infrastructure. Constructed through a combination of public funds, corporate donations, and countless volunteer hours, the Dome embodies Springerville’s capacity for collective action. Similarly, Ramsey Park serves as the community’s outdoor living room, hosting everything from family picnics to summer concerts, Little League games to Veterans Day observations.

Informal gathering places hold equal importance in community life. The El Rio Café has served as an unofficial town hall since 1950, with particular tables known to be the domain of specific groups—ranchers gather near the front window, while a back corner hosts retired teachers most weekday mornings. Perkins Hardware maintains a woodstove where customers linger during winter months, exchanging news and advice. These unplanned social spaces facilitate the information sharing and relationship building that sustain small-town cohesion.

Sacred spaces also function as community anchors. The Community Presbyterian Church, St. Peter’s Catholic Church, and the LDS Ward buildings serve their congregations while providing venues for broader community activities. The annual interfaith Thanksgiving service rotates between these locations, symbolizing the community’s ability to transcend denominational differences when addressing shared concerns.

These gathering places hold layers of memory and meaning for residents. The high school auditorium isn’t simply a performance venue but the site of decades of graduations, talent shows, and community debates. Becker Lake isn’t just a fishing spot but the location of countless family outings and teenage rites of passage. These shared associations with physical spaces create a geography of memory that binds residents to place and to each other.

Springerville has faced substantial challenges throughout its history, testing the community’s adaptability and determination. Early residents contended with isolation, harsh winters, and conflicts over land and water rights. The Great Depression hit the region particularly hard, with drought compounding economic hardship for ranching families. More recently, the Wallow Fire of 2011—the largest wildfire in Arizona history—threatened the town itself while devastating surrounding forests, demonstrating the vulnerability of mountain communities to environmental change.

Contemporary challenges include economic uncertainties, particularly as traditional industries evolve. The planned transition away from coal power threatens jobs at the nearby generating station, while changing precipitation patterns impact ranching operations. The community’s aging population creates concerns about healthcare access and volunteer capacity for essential services, while limited housing options make it difficult for young families to establish themselves locally.

Stories of resilience permeate community identity. Longtime residents recall how the town rebuilt after the flash flood of 1940 washed away bridges and buildings, with neighbors housing displaced families for months. The community weathered the closing of the timber mill in the 1980s, diversifying its economy rather than surrendering to decline. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated Springerville’s self-sufficiency, as neighbors established support networks for vulnerable residents and local businesses adapted to serve essential needs.

These experiences have fostered a pragmatic optimism in Springerville—a belief that while challenges are inevitable, the community possesses the resources and determination to overcome them. This resilience isn’t romanticized but is instead understood as the practical outcome of strong social bonds, diverse skills, and a shared commitment to place that transcends individual interests.

Springerville approaches its future with a characteristic blend of practicality and respect for tradition. Rather than viewing preservation and progress as opposing forces, the community seeks balanced development that builds upon existing strengths while adapting to changing circumstances. This approach is evident in the Springerville Master Plan, which prioritizes maintaining the town’s distinctive character while addressing needs for economic diversification, housing, and infrastructure improvements.

Historic preservation efforts focus on both buildings and cultural practices. The Main Street Enhancement Program has helped business owners maintain historic facades while upgrading interiors to meet contemporary needs. The Heritage Skills Program pairs youth with elders to ensure traditional crafts and practical knowledge continue into future generations. These initiatives reflect Springerville’s understanding that authenticity cannot be manufactured but must instead be thoughtfully maintained.

Residents’ hopes for Springerville’s future consistently emphasize sustainability—not just environmental but economic and cultural. They envision a community that remains affordable for working families, where young people can find meaningful livelihoods without leaving. They desire economic development that complements rather than replaces traditional industries, building on the community’s outdoor recreation assets without surrendering to outside interests or commodifying local culture.

Most fundamentally, Springerville residents hope to maintain the quality of relationships that define small-town life while adapting to inevitable changes. They recognize that new technologies, demographic shifts, and economic transitions will reshape their community, but they remain committed to preserving the core values that have sustained Springerville through previous transformations—neighborliness, self-reliance, and a deep connection to the land that has nourished generations.

What gives Springerville its distinctive character isn’t simply its historic buildings, natural setting, or annual events, but the intangible qualities that emerge from the community’s shared experiences and values. Residents from diverse backgrounds consistently identify certain essential attributes when describing what makes their town special. Elderly ranchers speak of the “neighbor principle”—the unspoken understanding that help will be given and received without hesitation when needed. Young parents value the “extended family” quality of a community where children are watched over by numerous adults. Newcomers describe the balance of privacy and connection—the ability to establish independence while being genuinely welcomed into community life.

This sense of belonging transcends typical social divisions. As one Hispanic business owner expressed, “In Springerville, we’re all high-country people first—that means something.” A descendant of Apache people noted that while historical injustices aren’t forgotten, there’s “a shared respect for anyone who truly knows and loves this land.” These sentiments reflect how place and common experience create bonds that complement and sometimes transcend cultural backgrounds.

Ultimately, Springerville’s soul resides in its remarkable combination of toughness and tenderness—the ability to endure difficult conditions while maintaining compassion for neighbors. It lives in the community’s habit of gathering to celebrate achievements, mourn losses, and address challenges together. And it continues through the conscious choice of each generation to remain in—or return to—this remote mountain town, contributing to its ongoing story while drawing strength from its deep roots. In an increasingly standardized world, Springerville stands as testament to the enduring importance of place, heritage, and community connection.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By using our site, you consent to cookies.

Manage your cookie preferences below:

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.